| 史上最差潛艇,092夏級在列。 |

| 送交者: SDUSA 2014年02月03日08:13:05 於 [軍事天地] 發送悄悄話 |

|

全文見:http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/the-five-worst-submarines-all-time-9803

Herewith, History's Worst 5 Submarines, listed from least bad to worst of the worst: 5. Thresher, Scorpion, and Kursk Why the hodgepodge? These are boats that sank under puzzling circumstances, damaging a great-power navy's reputation for excellence at a time when reputation truly mattered. Because it's hard to say for sure what happened -- whether equipment or human failure was more blameworthy -- these disparate boats belong in a class of their own.

What we do know is that the accident sent the U.S. Navy scurrying for answers -- and trying to mend the silent service's esteem -- at a critical juncture in the Cold War. The Cuban Missile Crisis was a recent memory, while Admiral Sergei Gorshkov's Soviet Navy was embarking on a crash buildup. Clausewitz portrays military competition as a "trial of moral and physical forces" -- of strength, on other words -- "through the medium of the latter." The death of Thresher worked against the idea of U.S. undersea mastery -- heartening Moscow for the zero-sum contest between East and West.

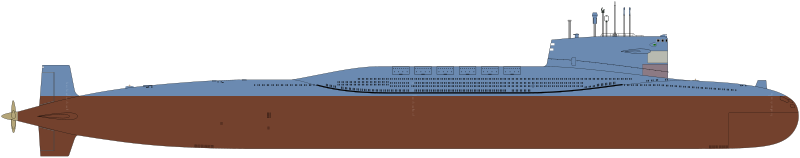

The lesson from these sinkings and similar debacles--think last year's explosion on board the Indian diesel boat Sindhurakshak--is sobering for navies. When a ship becomes a symbol, its death has outsized political and even cultural ramifications. Failures in seamanship or everyday routine, then, can reverberate far beyond a boat's hull. 4. Type 092 Xia You can say one good thing about the next boat on the list: it hasn't sunk. On the other hand, China's first SSBN has done little to advance its chief mission, nuclear deterrence. The lone Xia entered service in 1983. Its crew finally managed to test-fire an intermediate-range JL-1 ballistic missile in 1988, overcoming debilitating fire-control problems. Yet the boat has never made a deterrent patrol and seldom leaves the pier. Retired submarine commander William Murray describes the Xia -- and the Han SSNs from which its design derives -- as "aging, noisy, and obsolete."

3. K-class submarines When new technologies appear, navies habitually deploy them as fleet auxiliaries -- that is, to help the existing fleet do what it's already doing, except better. Undersea craft were no exception a century ago, when navies were still experimenting with them. The Royal Navy's World War I-era K-class boat was a failed experiment, as the nicknames affixed to it--Kalamity, or Katastrophe--attest. Designed in 1913, these boats were meant to range ahead of the surface fleet, screening the fleet's battlewagons and battlecruisers against enemy torpedo craft. Or they could seize the offensive, softening up the enemy battle line before the decisive fleet encounter. A solid concept. But to keep up with surface men-of-war, such a boat would need to travel at around 21 knots on the surface, faster than any British sub yet built. Diesel engines were incapable of driving a boat through the water at such velocity. The Admiralty's speed requirement, therefore, demanded steam propulsion. However sound the tactics behind the K-class, outfitting subs with steam plants was a bad idea. Ask any marine engineer. Boilers gulp in air, they generate prodigious amounts of heat, and they emit exhaust gases in large quantities. Trying to submerge a steamship, consequently, means trying to submerge a hull with lots of intakes and smokestacks. Unsurprisingly, the K-class leaked. The heat was torrid while underwater. It wallowed in rough seas, and displayed a troublesome reluctance to pull out of a dive. Of 18 K-class boats, none was lost to enemy action. But six -- a full third of the class -- were lost to accidents. The most gallant, astute crew can achieve little with hardware that is backward. Never again did the Royal Navy establishment foist a conventional steam-powered boat on British tars. 2. K-219. This Yankee-class Soviet SSBN suffered an explosion and fire in a missile tube in 1986, while cruising some 600 miles east of Bermuda. It occupies an ignominious place on this list because of the repercussions of losing a ballistic-missile boat -- a vessel stuffed with nuclear firepower -- and because by most accounts the mishap was needless. Here, as with the travails of the K-class boats, blame lies at the feet of obtuse senior leaders. Such failings annul even capable platforms.

Kurdin and Grasdock observe, second, that the Soviet Navy was lackadaisical about safety by comparison with the U.S. Navy. (To its credit, the U.S. silent service got religion in the wake of the Thresher and Scorpion incidents, instituting its SUBSAFE program.) Evidently, they write, the explosion and fire may not have occurred "if one more person had checked the last maintenance performed on missile tube No. 6." In short, to keep up appearances in the late Cold War, Moscow and the naval establishment imposed an operational tempo on the SSBN force that prompted submariners to cut corners on basic standards. The result: a black eye for the Soviet Union, a superpower in retreat. Here again, neglect of the fundamentals had major political import. 1. Imperial Japanese Navy submarine force. Granted, it seems unfair to indict an entire silent service on this list. But what did IJN submarines accomplish against the U.S. Pacific Fleet during World War II, when the American war effort depended on long, distended sea lanes vulnerable to undersea assault? Not much. Subpar performance resulted not from a shortage of capable boats or skillful, resolute sailors -- by most accounts Japanese fleet boats were the equals of the Gato-class boats that spearheaded the U.S. submarine campaign--but from a shortage of flexibility and imagination among top commanders. As noted before, navies tend to use unfamiliar technologies as auxiliaries. So it was with Japan. But whereas some services innovate over time, the IJN leadership proved stubbornly shortsighted. For decades, commanders had marinated themselves in a bowdlerized version of Alfred Thayer Mahan's works. In particular, they made a fetish of Mahan's advocacy of duels between big-gun warships. Having donned doctrinal blinkers, they could conceive of few ways to employ subs beyond supporting the battle fleet. Rather than inflict mayhem on U.S. logistics--much as the German Navy did in the Atlantic, and much as the U.S. Navy did against Japanese sea lanes in the Western Pacific--the IJN allowed transports, tankers, and other vital but unsexy shipping to pass to and fro unmolested. Vast quantities of American war materiel traversed the broad Pacific--letting American forces surmount the tyranny of distance.

For which U.S. military veterans everywhere are eternally grateful. When shipping out for oceanic battlegrounds, it's good to face history's worst subs. The Imperial Japanese Navy submarine force is hereby designated Bottom Gun. James Holmes is Professor of Strategy at the Naval War College and co-author of Red Star over the Pacific, named Essential Reading on the Navy Professional Reading List. The views voiced here are his alone. |

|

|

|

| 實用資訊 | |

|

|

| 一周點擊熱帖 | 更多>> |

| 一周回復熱帖 |

| 歷史上的今天:回復熱帖 |

| 2013: | 韓國不甘寂寞展示KF-X/IF-X隱型機最新 | |

| 2013: | 俄澳專家:殲20大載彈量內置六航彈 超 | |

| 2012: | 淮海戰役徵用540萬民工是得民心還是壓 | |

| 2012: | 長津湖之戰中美軍屍體(組圖)zt | |

| 2011: | 真實的第五次戰役志願軍大潰敗實錄-摘 | |

| 2011: | 新年寄語:必須對台島灣民嚴加管教 | |

| 2010: | 世界笑柄:中國戰略失誤,有王牌也不敢打 | |

| 2010: | 應對美國向台灣出售武器的唯一正確辦法 | |

| 2009: | 香椿樹:只有社會主義能夠救索馬里 | |

| 2009: | 曹長青:台灣的新紀元 (新大圖) | |