Washington, D.C. trade publication Aviation Week has confirmed what its top reporters and other observers long suspected: the U.S. Air Force has tested—and is preparing to buy in substantial numbers—a stealthy, long-range reconnaissance drone meant to boost America’s ability to spy on even the most heavily-armed rival nations.

Examining contractor financial statements in the context of secretive Air Force base construction and veiled comments by senior military officials,AvWeek’s Bill Sweetman—one of the world’s top aerospace reporters—along with veteran colleague Amy Butler out the Northrop Grumman-built RQ-180 drone in the magazine’s Dec. 9 issue.

The approximately 130-foot-wingspan autonomous vehicle is based on the radar-dodging “cranked-kite” form preferred by Northrop designers—and is probably intended to be jointly operated by the Air Force and Central Intelligence Agency, according to Sweetman and Butler. Read their whole report here.

The RQ-180 apparently began development as long as nine years ago and, when it enters production in or around 2015, could complement the smaller RQ-170 stealth drone—itself outed in 2009—and fully replace the Global Hawk, an older Northrop robot that the Air Force has been keen to retire.

The existence of the new Northrop spy drone also helps explain why Lockheed Martin has been pushing its concept for a Mach-6 reconnaissance UAV dubbed the “SR-72.” Lockheed could feel threatened, for with the RQ-180, Northrop has taken a potentially huge leap forward in stealth and drone technology.

To be sure, it was a leap with a long running start … beginning nearly 15 years ago.

Stealth imperative

In the early 2000s, American drone operators were in for a nasty surprise. In the 1990s U.S. Predator UAVs spying on the Balkans conflict had faced stiff resistance from Serbian troops — and several of the prop-driven robots were shot down. But in the years since over Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia and The Philippines, the Predator drones hunted essentially defenseless enemies. The Pentagon and CIA had grown accustomed to total freedom of action.

Then came the run-up to the 2003 Iraq war.

Iraq was no Somalia. It possessed a functioning army and air force and the will to use them. On many occasions when U.S. drones crossed into Iraqi air space, Iraqi jet fighters rose to intercept. Saddam Hussein’s MiGs were making it hard for the UAV crews to complete their missions.

The Air Force sought a temporary fix in fitting Stinger air-to-air missiles to some Predators. That effort ended in embarrassment for the flying branch in December 2002 when a Predator confronted an Iraqi MiG-25 fighter — and was promptly knocked out of the sky as its Stinger missile trailed off into the distance.

The Pentagon had a better, long-term solution to the UAV vulnerability problem: a new drone able to evade enemy radars, penetrate air defenses and survive against even the most determined foe. The stealthy UAV would be the first in a new lineage of high-tech drones that today is remaking aerial warfare.

Developed and deployed in secret, the new robot warplanes have left a trail of bread crumbs in the form of industry contracts, squadron patches, crash-site wreckage and surreptitiously-snapped photographs.

One new drone has been revealed. And another secretly prowls the skies over America's enemies.

Dark Star down

Despite crashes and shoot-downs, the Pentagon was happy with the Predator’s performance over the Balkans in the mid-'90s. And in 1995 the military dramatically expanded on the drone concept.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the military’s fringe-science wing, commissioned two new UAV designs required to fly higher and farther than the Predator. The total cost: $400 million to develop and test fly several prototypes of each model within three years’ time.

The new ‘bots included one type optimized for altitude, and another that would fly lower but also include radar-evading stealth elements. Both were public efforts, routinely detailed in government press materials and widely discussed in the media.

San Diego-based aerospace firm Teledyne Ryan — later acquired by Northrop Grumman — snagged the contract for the high-flyer, which it dubbed “Global Hawk.” Today Global Hawks are in use all over the world, keeping watch on battlefields, terror hotspots and disaster zones.

The lower-flying stealthy drone model became known as “Dark Star.” Boeing and Lockheed Martin teamed up to produce the prototype, which took off on its debut flight at Edwards Air Force Base in California in March 1996. On its second flight in April, the Dark Star drone malfunctioned and crashed. Boeing and Lockheed built several more copies, but in 1999 the Pentagon cancelled the effort.

Except not really. The Dark Star concept and some of the technology survived in modified form. Lockheed quietly assembled the stealthy drone’s high-tech successor in total secrecy. No outsiders would know anything about it until eight years later.

At first the only clue — and an oblique one at that — was a patent for an unmanned aircraft filed in 1997 by the Texas plane-maker. A sketch included with the patent showed a single-engine, swept-wing robot with a bulbous body and the sharp wing edges associated with stealth designs.

Very few knew it, but by 2002 the stealth drone was almost ready for combat. It would greatly expand the reach of America’s robotic strike force in Iraq and across the globe, laying the groundwork for future robotic warfare and, by extension, the shadowy wars that would follow America’s disastrous ground campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Assigned to spy on Iraq in 2002, the new UAV was never officially acknowledged. But it was seen.

The pilots of high-flying U-2 spy planes, based in the United Arab Emirates for reconnaissance flights over Iraq, complained of nearly colliding with unidentified but obviously U.S.-origin drones flying along similar paths as the venerable U-2s.

David Fulghum, a reporter for the trade publication Aviation Week, caught wind of the U-2 pilots’ gripes and managed to eke a few anonymous comments from Pentagon sources. An Air Force official told Fulghum that the flying branch possessed a new, secret UAV, built by Lockheed Martin using parts scavenged from the defunct Dark Star and other aerospace programs dating back to the mid-’90s.

“It’s the same concept as Dark Star,” the official told Fulghum. “It’s stealthy, and it uses the same apertures and data links.”

“The numbers are limited,” the source added. “There are a couple of airframes, a ground station and spare parts.”

The new drone’s sensors reportedly included a radar, a daylight camera and an infrared imager. It could fly for up to eight hours at a time. Its ability to absorb or deflect radar energy away from ground-based emitters meant it could fly deep inside enemy defenses where other reconnaissance aircraft dared not venture.

Fulghum speculated that the secret drone was based at Al Udeid air base in Qatar, where the Air Force had roped off some hangars to keep inquisitive reporters away. He did not, however, speculate as to the new robot’s designation. That would not be revealed for another seven years.

Secret squadron

The chain of revelations began apparently by accident.

On Sept. 1, 2005, at the highly-secure Tonopah Test Range in Nevada, a base that had once housed the Air Force’s secretive fleet of F-117 stealth fighters, the flying branch quietly reactivated the 30th Reconnaissance Squadron, an aerial photography unit that had been defunct since the 1970s.

The Air Force kept the revived squadron’s existence a secret for seven months. In a March presentation to a group of civilians at nearby Nellis Air Force Base, 1st Lt. Justin McVay flashed a slide listing Air Force Predator squadrons. The 11th, 15th and 17th Reconnaissance Squadrons and the 3rd Special Operations Squadron had all been previously disclosed, but the slide also referenced the “30th RS.”

After the presentation, reporter Keith Rogers asked McVay about the 30th RS and was told its operations were classified. What McVay did not say, and may not have even known, was that the 30th was the operating unit for the new, stealthy spy drone that Lockheed Martin had salvaged from the ruins of the canceled Dark Star UAV and which had nearly collided with manned U-2 recon planes over Iraq two years prior.

On July 17, 2007, just short of a year after McVay’s admission, the Air Force approved a new uniform patch for the 30th RS that featured a predatory bird perched atop a globe of the world, its claws straddling Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran.

Sometime the same year, a photographer on assignment to cover French army operations in southern Afghanistan was on the flight line at Kandahar Air Field, NATO’s major base in the region, when he spotted something curious: what appeared to be a flying-wing drone, flying overhead and taxiing along the runway.

The photog apparently knew enough about UAVs to know that the vehicle before him was of a type that had never been reported before. Under the media embed rules, no picture-taking is allowed on the Kandahar flight line, but the photographer took a chance, and snapped several long-range shots.

And then sat on them for no less than a year.

In April 2009 one of the photos was shown to Darren Lake, a reporter forUnmanned Vehicles magazine. Lake published a story hailing the debut of “a new, advanced but as yet undisclosed UCAV,” or Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle.

In May the French magazine Air & Cosmos published one of the blurry photos depicting the drone in flight, and provided another, similar image toAviation Week, where veteran aerospace reporter Bill Sweetman dubbed the mysterious machine the “Beast of Kandahar.”

Seven months later the French newspaper Liberation published yet another snapshot, this one much clearer and showing the Beast on the ground.“Gotcha,” Sweetman wrote.

Three days later on Dec. 4, 2009, the Air Force responded to Aviation Week’s queries with the biggest aviation scoop in years. The Beast of Kandahar was really the RQ-170 Sentinel, “a stealthy unmanned aircraft system to provide reconnaissance and surveillance support to forward deployed combat forces.”

The Sentinel was flown by the 30th Reconnaissance Squadron, the Air Force admitted.

The aviation media went wild speculating on the drone’s origins, capabilities and purpose. Sweetman zeroed in on the most compelling question. The Air Force seemed to imply the Sentinel was being used against the Taliban and Al Qaeda in Afghanistan. “Why use a stealth aircraft against an adversary that doesn’t have radar?” Sweetman asked.

In truth, the Sentinel wasn’t being used against the Taliban at all. For the radar-evading drone, Iraq had been a sideshow and Afghanistan was a front; its real targets were some of the most hidden and heavily protected in America’s expanding shadow wars.

Eyes everywhere

The implications of the Sentinel’s debut were enormous.

When the Pentagon oversaw the initial development of the Predator, the larger Global Hawk and the Dark Star, it ranked the three vehicles by order of vulnerability. Owing to its slow speed, low altitude ceiling, and lack of defensive systems, “the Predator is the most vulnerable of the three platforms to hostile threats,” the Defense Department concluded.

Sure enough, the Serbs and Iraqis between them had shot down several Predators, even shooting one up with a machine gun fired through the open window of a helicopter cruising alongside the drone.

The high-flying Global Hawk was considered better protected than the Predator but still vulnerable to the best surface-to-air missiles. Only the Dark Star, with its high ceiling, jet power, and radar-evading qualities, would be able to “accomplish a penetration surveillance and reconnaissance mission in an integrated air defense system environment,” the Pentagon asserted.

Prior to December 2009 only the Predator and Global Hawk were known to be in service, meaning the acknowledged extent of U.S. military and, by extension, CIA drone ops was necessarily limited. The Americans’ robots could only probe the least-defended airspace. Countries like Iran and North Korea were most likely off limits. A Global Hawk or Predator could only surveil around those countries, not directly over them.

In one fell swoop, the Sentinel’s debut altered this understanding of the U.S. government’s reach. Where once large swaths of the world appeared to be off limits to the Pentagon and CIA’s probing eyes and deadly missiles, with the Sentinel’s appearance it was clear no country was truly and completely drone-proof.

At the moment the Sentinel entered service, sometime before 2003, the Americans possessed the ability to spy on, and in theory strike, targets anywhere in the world.

Within days of the Air Force confirming the Sentinel’s existence, a South Korean newspaper reported that the stealthy 'bot was being deployed to the Korean peninsula to spy on the North.

And in the hours after Osama Bin Laden was killed by U.S. Navy SEALs in his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, National Journal’s Marc Ambinder, got a tip on the Sentinel’s involvement in that mission. “RQ-170 drone overhead,” Ambinder wrote on Twitter.

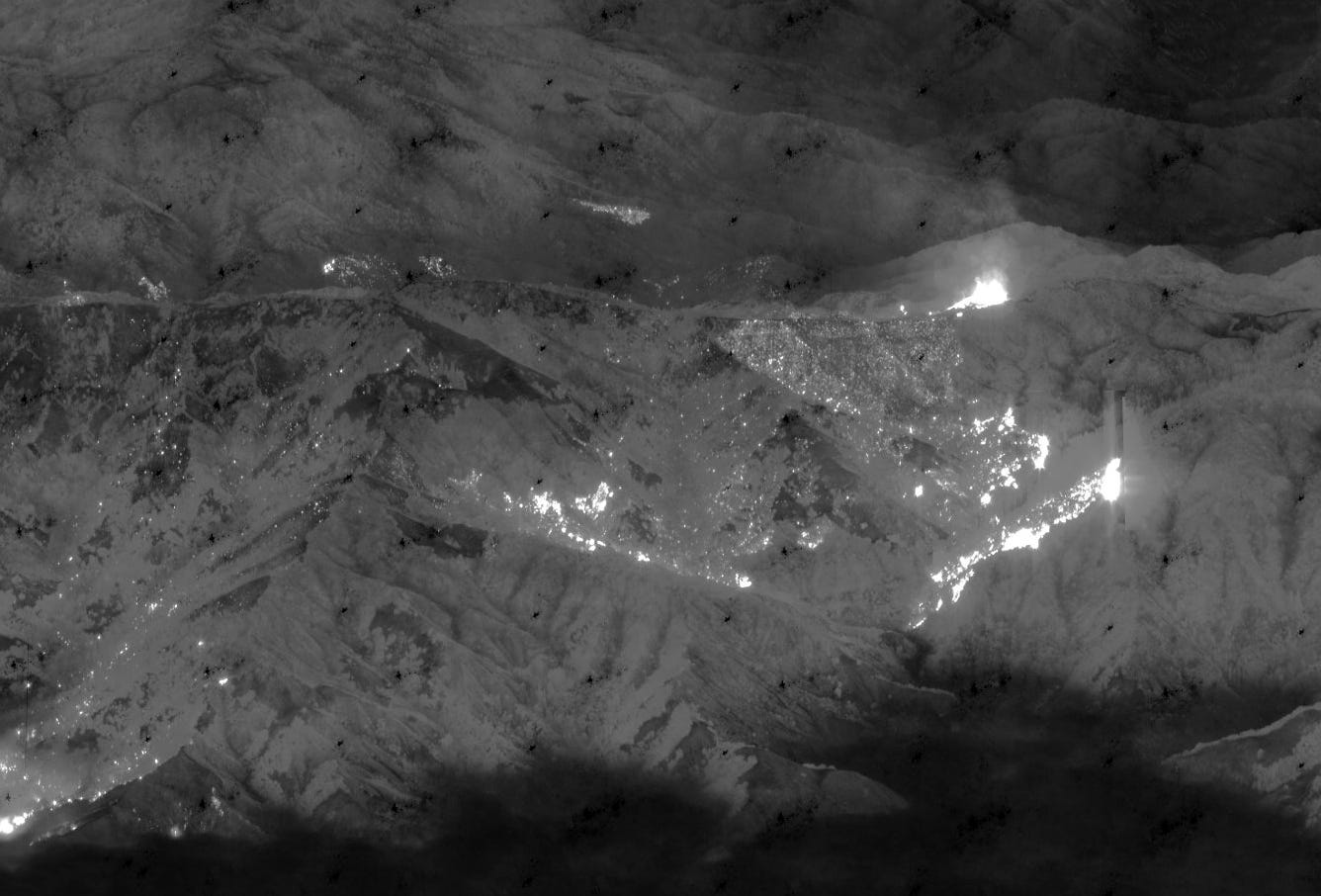

And seven months later on Dec. 4, Iranian state media reported that the country’s army had forced down an American drone inside its airspace. The accompanying photos and video left no doubt: the Iranians had captured a partially-wrecked Sentinel that had somehow malfunctioned, probably while overflying Iranian airspace that was defended by overlapping radars, surface-to-air missiles and jet fighters.

The capture belied a chilling reality for America’s enemies. U.S. drones — one model, at least — were now anywhere and everywhere Washington wanted to watch and listen. The Sentinel's capture by Iran had given U.S. rivals a chance to inspect the latest drone technology and possibly devise new defenses, allowing them to catch up somewhat to America’s distant lead in the drone arms race.

But not for long. For even as Iranian, Russian and Chinese engineers dismantled the crashed RQ-170, American engineers were apparently putting the finishing touches on an even newer and better radar-evading UAV.

Next generation

In December 2012 Aviation Week journalist Sweetman concluded that Northrop Grumman had been working on a large, armed UAV for the Pentagon and CIA — one with greater speed, payload, range and stealth than the current drones. It’s this robot that Sweetman and Butler would eventually reveal as the RQ-180.

Development began in 2008, Sweetman surmised, based on his analysis of company documents and interviews with industry insiders. “It is, by now, probably being test-flown at Groom Lake,” Sweetman wrote of the new drone.

The purported location, at least, made total sense. The Air Force’s secret facility in Groom Lake, Nevada, is part of the so-called “Area 51” complex and previously was the test site for the U-2 and SR-71 reconnaissance planes and the F-117 stealth fighter.

If real, the in-development drone could help explain some peculiar moves by the Air Force in 2012 and 2013. The flying branch proposed to abandon almost all of its essentially brand-new Global Hawk UAVs while also cutting production of the smaller Reaper drones.

Congress ultimately nixed both proposals, but the Air Force’s willingness to part with its some of its publicly acknowledged drones was possibly indicative of a brand-new ‘bot preparing to enter service and take over from the older models.

There was plenty of precedent for covert drone development. The Sentinel, of course, was developed in total secrecy by Lockheed Martin and flew combat missions for around five years before breaking cover.

Likewise, Lockheed and rival Boeing both secretly designed and built large, stealthy, jet-powered UAV demonstrators for a Navy effort to add drones to aircraft carrier decks — an initiative Northrop was also openly supporting with a drone prototype of its own.

The new Boeing and Lockheed naval drones, which both bore a superficial resemblance to the Sentinel (as did Northrop’s less secretive naval UAV prototype), were unknown to the outside world except as rumors until the companies unveiled them as part of their sales efforts. Northrop’s purported new UAV was probably meant to build on the concepts explored by the fast, radar-evading Sentinel.

Sweetman estimated only around 20 Sentinels were built in the early 2000s as a stopgap measure pending the introduction of Northrop’s more high-tech robot sometime in the mid-2010s. In 2008, the company’s financial documents listed a $2-billion “restricted programs” contract that Sweetman believed was the development deal for the new drone.

Around the same time, Northrop hired as a consultant John Cashen, the man most responsible for designing the radar-defeating shape of the company’s older B-2 Spirit stealth bomber.

Not coincidentally, in 2009 Northrop filed patents for two variants of a new manned stealth bomber design, both sharing the same tailless flying-wing shape as the company’s B-2 and Pegasus naval drone prototype.

Northrop’s other efforts apparently influenced the secret drone design. “It is believed to be a single-engine aircraft with a wingspan similar to a Global Hawk,” Sweetman wrote of the new UAV. A Global Hawk spans 116 feet, making roughly as big across as a 737 airliner.

Consistent with the three-year-old patents, Sweetman contended that the secret UAV likely included radar, electronic surveillance systems and radar jammers and, quite possibly, a bomb bay for carrying guided bombs.

Sweetman’s conclusions were just speculation, albeit highly informed speculation. But with a classified budget of no less than $30 billion a year, the Pentagon — to say nothing of the even more opaque CIA — was undoubtedly working on a host of advanced drone designs.

Northrop’s new RQ-180 ‘bot just had the most detectable paper trail. Whether and when this and other secret drones would be officially revealed to the public was, according to Sweetman, “anyone’s guess.”

Possibly the first member of the public to glimpse Northrop’s new robot, or something similar, did not realize what he was looking at.

In mid-2011 a freelance photographer — I agreed to withhold his name — was visiting the Air Force’s Tonopah Test Range in Nevada, a somewhat less secretive adjunct to Groom Lake.

While walking along the tarmac with an officer guide, the photographer spotted, some 150 yards away, what appeared at first to be a Sentinel drone parked in an open hangar. But upon closer inspection, the photog noticed details inconsistent with the recently-revealed Sentinel.

The engine air intake was different. The skin material seemed less metallic. And the craft was apparently much bigger than the Sentinel, which by then had appeared only in grainy photos taken in Afghanistan. (Tehran’s capture of a crashed Sentinel was still a few months off, but the photographer later said that the details revealed by Iranian footage of the wrecked UAV only confirmed his earlier impressions.)

It was clear the Air Force had not intended the photographer to see the new ‘bot, whatever it was. The colonel leading the tour grew uncomfortable. “I was specifically asked not to photograph it and I complied,” the photog said of the mystery drone.

Recalling the encounter, the photographer concluded he had seen a new variant of the Sentinel. He was not aware at that time that Northrop was developing, and the Air Force and CIA were testing in and around Area 51, a brand-new, larger and better UAV.

It’s possible that’s what he saw. The RQ-180. The secretive future of drone warfare, long in development and finally outed by the press.

My new book Shadow Wars is out. Sign up for a daily War is Boring email updatehere. Subscribe to WIB’s RSS feed here and follow the main page here.