| 一篇膚淺迴避要害為石正麗團隊洗地英文報道 | |||

| 送交者: Pascal 2020年02月10日03:22:36 於 [五 味 齋] 發送悄悄話 | |||

|

Mining coronavirus genomes for clues to the outbreak’s origins

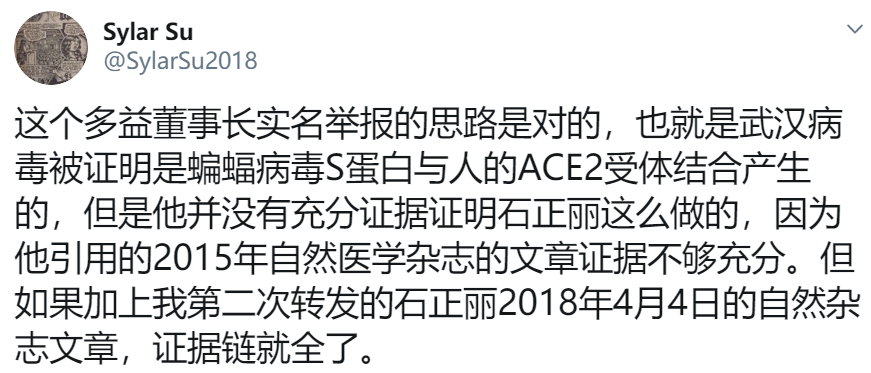

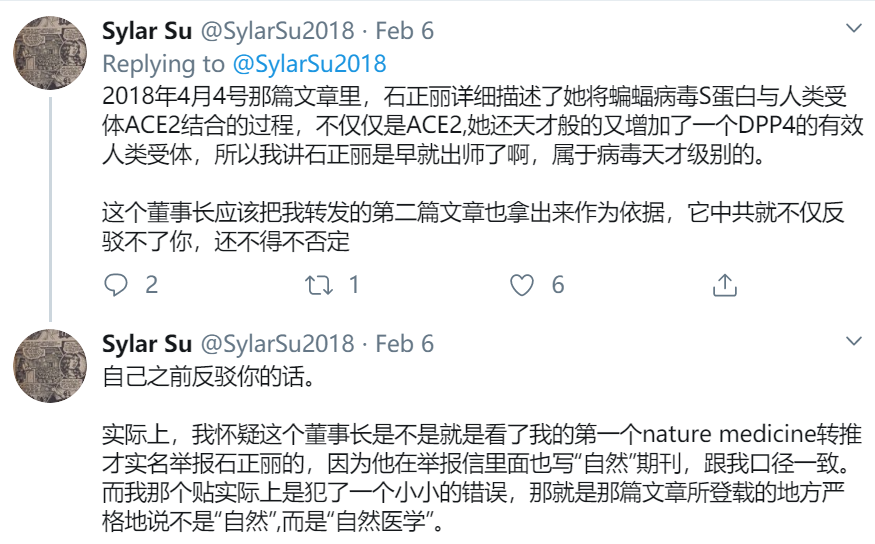

attaaaggtt tataccttcc caggtaacaa accaaccaac tttcgatctc ttgtagatct … That string of apparent gibberish is anything but: It’s a snippet of a DNA sequence from the viral pathogen, dubbed 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), that is overwhelming China and frightening the entire world. Scientists are publicly sharing an ever-growing number of full sequences of the virus from patients—53 at last count in the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data database. These viral genomes are being intensely studied to try to understand the origin of 2019-nCoV and how it fits on the family tree of related viruses found in bats and other species. They have also given glimpses into what this newly discovered virus physically looks like, how it’s changing, and how it might be stopped. 本文第一次提及2019新型冠狀病毒族譜系最接近蝙蝠攜帶的病毒。 “One of the biggest takeaway messages [from the viral sequences] is that there was a single introduction into humans and then human-to-human spread,” says Trevor Bedford, a bioinformatics specialist at the University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. The role of Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China, in spreading 2019-nCoV remains murky, though such sequencing, combined with sampling the market’s environment for the presence of the virus, is clarifying that it indeed had an important early role in amplifying the outbreak. The viral sequences, most researchers say, also knock down the idea the pathogen came from a virology institute in Wuhan. 老張推崇的病毒科學來了:murky 一詞屬於含糊其辭,閃爍其詞,雲山霧罩在先,肯定武漢華南海鮮批發市場售賣的野生動物為病毒 vector 載體傳至人體在後。而問題的細節尚未展開,本段落最後一句,就甚為乾脆武斷地、借大多研究者之名聲稱,病毒基因序列顯示,其病原體與武漢P4實驗室概無干係。 作者 Jon Cohen 行文至此,觸及了一個很有意思的事情:五天之前,1月26日,正是他本人撰文寫道:

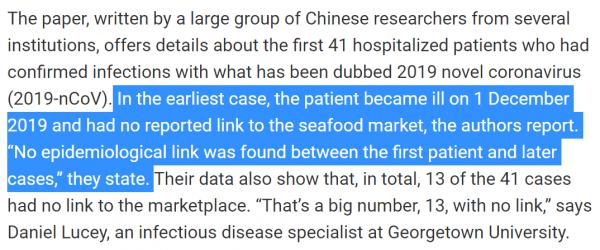

原來,去年12月1日住院確診的第一位新型冠狀病毒患者,壓根兒就沒去過那個海鮮市場!所以,他感染的pathogen病原體來自何方? 中英論文文字記載里,沒有比他被確診時間更早的了,也沒有誰能比他更有說服力為蝙蝠俠還一個清白。因為,武漢人不吃蝙蝠,那段視頻裡的浙江衛視主持人汪夢雲自己事後都說道歉誤導了大家。

第一位患者與海鮮市場無關卻感染上了,馬上導致人傳人,傳進海鮮市場後感染多位,又傳了出來。 說 Jon Cohen 這一篇文實在膚淺,下述這麼簡單的事實,作者 卻視而不見,還是聞所未聞?對此,又該如何解釋圓滿呢?

後面的內容,以石正麗團隊的角度、 以新華社提供的口徑撰文,就是 隻字不提西陸網認可的要害問題:

.........................................

******************************************************************

美國病毒學家牽頭聯合中國病毒專家 就曾合作成功提取和鑑定出了一種類SARS 新型冠狀嵌合病毒,並且之後又人工製造和 培養出了一種SARS新型冠狀重組病毒。 這份研究報告由美國學者和中國學者聯合完成, 作者包括美國德克薩斯大學醫學分校微生物與 免疫學系 教授Vineet D. Menachery ,中科院 武漢病毒研究所研究員石正麗(Zhengli-Li Shi) 等人,提取發現並又製造培養了一種嵌合型 SARS樣 的新型冠狀病毒 ...... ...... 基於以上這些發現, 上述科學家們最終成功合成了一株具有感染性的 全長SHC014重組病毒, 並同時在體外和體內證實了該病毒的強大複製能力。 成功地人工合成、製造、培養出了 一種新型冠狀重組病毒!

由中國武漢開始爆發的新型冠狀病毒肺炎疫情持續引發關注,從 1 月 21 日開始證實新冠病毒肯定有“人傳人”之後,一場全民參與的抗疫戰役在中國,乃至世界正式打響。目前已知 2019 年 12 月開始,從第一起華南海鮮市場病例被證實,與SARS冠狀病毒極為類似的“不明病毒肺炎”新型冠狀病毒開始蔓延。 但是鈦媒體最近在仔細研究和整理新冠病毒相關研究時也發現,其實早在 5 年前,也就是 2015 年,美國病毒學家牽頭聯合中國病毒專家就曾合作成功提取和鑑定出了一種類SARS新型冠狀嵌合病毒,並且之後又人工製造和培養出了一種SARS新型冠狀重組病毒。這次的研究成果也被發表在了2015年的國際頂級科學雜誌《Nature》上(下稱:Nature論文)。 在今年武漢爆發的新冠病毒肺炎發生之時,回過頭來再看這份五年前的研究報告,依然頗覺觸目驚心。雖然並不能證明五年前的研究發現和本次發生的武漢肺炎病毒是完全同一的病毒,但是的確都是與Sars極為相近的新冠病毒,在今年1月,有專家認為本次“不明肺炎”疫情,傳播速度快、重病率高、難以"防控”的態勢,是世界首次發生的時候,實際上,五年前就早有發生,而病毒科學家也早有預知,並且所有預知的內容都與本次發生的疫情狀況高度相似。 這份研究報告由美國學者和中國學者聯合完成,作者包括美國德克薩斯大學醫學分校微生物與免疫學系 教授Vineet D. Menachery ,中科院武漢病毒研究所研究員石正麗(Zhengli-Li Shi)等人,提取發現並又製造培養了一種嵌合型 SARS樣 的新型冠狀病毒,根據論文所述,該病毒能讓小鼠感染上 SARS(非典肺炎),也可以證實這一病毒通過蛋白外殼與體內 RNA 進行結合,感染和傳遞到人類細胞當中,報告結論就是這種類Sars新冠狀病毒,因其高度可人際傳播的屬性,可能會給人類帶來巨大的社會風險。 五年前的預言一語成讖,同時這份研究報告也說明,本次武漢疫情可能不是偶然的,類Sars冠狀病毒的變異和傳播從未停止,但人類並未重視。正如近日,北卡羅來納州吉林斯大學全球公共衛生學院的冠狀病毒專家兼助理教授蒂莫西·謝漢(Timothy Sheahan)評價武漢新冠肺炎所說,“這不是“一次性”的病毒疫情,很可能會在未來持續發生。” 針對近期沸沸揚揚的關於武漢病毒研究所的猜測和爭議,石正麗在其朋友圈發表聲明稱:“以生命擔保,2019新冠病毒與實驗室無關,這是大自然對人類不文明生活習慣的懲罰”。

武漢病毒研究所研究員石正麗 2015年到底發生了什麼?2015年的Nature論文中闡述了一個背景,即當時在中國有一個叫做馬蹄蝠的蝙蝠種群,這是一種在岩洞棲息地里的菊頭蝠科蝙蝠群體,它們體內正在流行一種類似SARS的病毒——SHC014-CoV,而當時嚴重急性呼吸綜合徵冠狀病毒(SARS-CoV)和中東呼吸綜合徵(MERS)-CoV的出現,突出了跨物種傳播事件對人類社會的威脅,故而科學家們希望研究在馬蹄蝠中流行的這一病毒的致病潛力。 蝙蝠是許多病毒的自然宿主,包括埃博拉病毒、馬爾堡病毒,狂犬病毒、亨德拉病毒、尼帕病毒等。由於蝙蝠特殊的免疫系統,攜帶病毒卻極少出現病症。在漫長的進化歷程中,蝙蝠成為了上百種病毒的自然宿主。對於病毒溯源的研究來說,蝙蝠地位很特殊,是重點的關注對象。 中國科研人員已發現,蝙蝠體內一個被稱為“干擾素基因刺激蛋白-干擾素”的抗病毒免疫通道受到抑制,這使得蝙蝠剛好能夠抵禦疾病,卻不引發強烈的免疫反應。野生蝙蝠可能會攜帶很多病毒,但是它們都維持在一個較低的水平上。 於是,Vineet D. Menachery教授等利用SARS-CoV的反向遺傳系統,從中提取並鑑定了一種嵌合病毒,該病毒在適應小白鼠的SARS-CoV主幹中可表達出蝙蝠冠狀病毒SHC014的刺突。結果表明,該新型冠狀病毒能利用SARS的人類細胞受體——血管緊張素轉換酶II(ACE2)的多個同源基因,在人類呼吸道原代細胞中有效複製,並在體外獲得與SARS傳染性同等的效果。 此外,體內實驗證明,該嵌合病毒被複製在小白鼠肺部後,可導致明顯的發病徵狀。評估顯示,現有的基於SARS的免疫治療和預防模式的效果不佳;單克隆抗體和疫苗方法均未能利用這種新的刺突蛋白來中和免疫CoVs感染。 基於以上這些發現,上述科學家們最終成功合成了一株具有感染性的全長SHC014重組病毒,並同時在體外和體內證實了該病毒的強大複製能力。研究結果表明,這種病毒完全可重現SARS-CoV(SARS冠狀病毒)的傳播風險。 Nature論文三種範例所證明的新冠病毒傳播原理,與武漢疫情高度類似以下都來自鈦媒體編輯翻譯並整理了上述2015年《Nature》論文中的主要分析內容,傳播原理的確與本次武漢新冠肺炎類似,很多結果也類似,例如關於致病性不會比Sars冠狀病毒增強、人傳人潛在風險極大(傳染性大)、老年動物(實驗主要以動物進行實驗)更易感等。 高致病性冠狀病毒SARS冠狀病毒的出現,預示着嚴重呼吸疾病跨物種傳播的新時代。全球化為病毒的快速傳播帶來基礎,對全球經濟有着巨大影響。 在SARS席捲全球後,甲型流感亞型病毒H5N1、H1N1和H7N9以及MERS冠狀病毒(中東呼吸綜合徵)開始出現,並且可以同樣通過動物傳染人類,對當地人口帶來了死亡的陰影以及經濟損失。 儘管公共衛生措施控制了SARS冠狀病毒的爆發,但最近的宏基因組研究通過識別近期在中國馬蹄蝠中大面積流行的類SARS冠狀病毒的病毒序列,發現這些由蝙蝠攜帶的病毒有可能在未來帶來更多的威脅。 但是,病毒序列帶來的數據只能為將來識別以及預防類似流行性病毒提供非常有限的洞見。因此,為了分析蝙蝠攜帶的冠狀病毒引起流行性傳播的可能性(也即是傳染人類的可能性),我們提取了中國馬蹄蝠攜帶的RsSHC014冠狀病毒序列中可造成人畜傳染的冠狀病毒刺穿蛋白,使用適應小白鼠的SARS冠狀病毒主鏈培育出了一種嵌合病毒。 培育出來的混合病毒讓我們能夠評估該刺穿蛋白在沒有經過自然適應性變異的情況下感染人類的能力。通過這個方法,我們對人類氣道細胞在活體狀態下由SHC014冠狀病毒導致的感染特徵進行了分析,測試了現有的免疫和治療方法對SHC014冠狀病毒的作用。這個研究方法能對宏基因組學數據進行解讀,幫助預防未來可能會出現的病毒,並未將來疫情爆發的可能性做好準備。 SHC014和相關的RsWIV1冠狀病毒的序列顯示,該類冠狀病毒為SARS冠狀病毒(圖示1a,b)的近親。但是,SHC014和SARS冠狀病毒在結合人類的14殘基和SARS冠狀病毒受體中存在差異。受體包括5個決定宿主範圍的殘基:Y442、L472、N479、T487和Y491 。在WIV1中,其中三個殘基與Urbani SARS冠狀病毒不同,按原本預期,它們不會改變和ACE2的結合。 這一情況由兩個假型化實驗得到證實。其中一個實驗測試了慢病毒屬WIV1刺穿蛋白進入細胞釋放血管緊張素轉換酶II(AC2)的能力。另一實驗為複製WIV1冠狀病毒(ref. 1)的試管實驗。在SHC014中存在14個與ACE2有相互作用的殘基,其中有7個殘基和SARS冠狀病毒的不一樣,這包括了所有5個對決定宿主範圍起關鍵作用的殘基。 這些變化,以及釋放SHC014刺穿蛋白進入細胞的慢病毒假型實驗,表明SHC014刺穿蛋白無法與人類的ACE2進行結合。 但是,有研究發現,其他相關的SARS冠狀病毒株存在類似變化,這意味着我們需要做進一步的功能測試才能做出更好的判斷。因此,我們基於複製功能強、實應小白鼠的SARS冠狀病毒主鏈合成了SHC014刺穿蛋白(該嵌合冠狀病毒在後文統稱為SHC014-MA15),以研究小白鼠的發病機理和疫苗研究。與現有分子建模和假型實驗得出的預測不同,SHC014-MA15保持了活性,並且在Vero細胞中複製致高滴度。 類似於SARS病毒,SHC014-MA15同樣需要功能正常的ACE2分子才能進入細胞,並且可以使用與人類、果子狸和蝙蝠直系同源ACE2。為了測試SHC014刺穿蛋白感染人類氣道的能力,我們研究了人類上皮氣道細胞系Calu-3 2B4對感染的敏感性,發現SHC014-MA15具有強大複製能力,與Urbani SARS病毒相當。 除此之外,人類主要氣道上皮(HAR)培養物被感染,兩種病毒都展現出了強大的複製能力。總之,這些數據證實了帶有SHC014的病毒感染人類氣道細胞的能力,並顯示出了SHC014冠狀病毒具備跨物種傳播的潛在威脅。

圖|SARS 樣的冠狀病毒在人類氣道細胞中複製並產生體內的發病機理 為了評估SHC014次突蛋白在體內介導感染中的作用,我們用104個SARS-MA15或SHC014-MA15空斑形成單位 (p.f.u.)感染了10周大小的BALB/c小白鼠(圖1e-h)。 感染SARS-MA15的白鼠在感染後第4天出現體重迅速下降和死亡現象(d.p.i.);而感染了SHC014-MA15的小白鼠體重下降顯著(10%),但無死亡(圖1e)。 對病毒複製的檢測顯示,感染了SARS-MA15或SHC014-MA15的小鼠肺部病毒滴度幾乎相同(圖1f)。感染了SARS-MA15的小白鼠的肺的末梢細支氣管和肺實質(圖1g)均有較強程度的染色(圖1g),而被SHC014-MA15感染的小白鼠的肺抗原染色較弱(圖1h);與此相反,在軟組織或整體組織評分中未發現抗原染色缺陷,這表示肺部組織對SHC014-MA15的感染情況有異(補充表2)。 感染SARS-MA15的動物體重迅速下降,並死於感染(補充圖3a,b)。感染SHC014-MA15可導致動物體重顯著下降,但致死率極低。在年輕小白鼠中觀測到的組織學和抗原染色模式,在年長些的白鼠中也可觀測到(補充表3)。我們使用Ace2−−老鼠進行實驗,排除了SHC014-MA15通過另一種感染受體傳播的可能性。 該種情況下,小白鼠沒有體重下降,或被SHC014-MA15感染後的抗原染色現象(補充圖4 a, b和補充表2)。以上這些數據表明,具有SHC014刺突的病毒能夠在CoV病毒主幹的條件下致使小白鼠體重減輕。 考慮到埃博拉單克隆抗體療法(例如 ZMApp 10)的臨床功效,我們接下來試圖確定 SARS-CoV 單克隆抗體對抗 SHC014-MA15 感染的功效。廣泛中和針對 SARS 冠狀病毒刺突蛋白已經被先前報道,並且是免疫試劑可能人類單克隆抗體。 我們檢查了這些抗體對病毒複製的影響(表示為病毒複製的抑制百分比),發現野生型 SARS-CoV Urbani 在相對較低的抗體濃度下被所有四種抗體強烈中和,SHC014-MA15的中和效果有所不同。通過噬菌體展示產生的和逃避突變型的抗體,僅實現抑制 SHC014-MA15 複製(如圖 2a)。同樣,源自 SARS-CoV 感染患者的記憶 B 細胞的抗體 230.15 和 227.14 也未能阻止SHC014-MA15複製(圖 2b,c)。 對於所有三種抗體, SARS 和 SHC014 尖峰氨基酸序列之間的差異對應於 SARS-CoV 逃逸突變體(fm6 N479R; 230.15 L443V; 227.14 K390Q / E)中發現的直接或相鄰殘基變化,這可能解釋了抗體的缺失針對SHC014的中和活性。 最後,單克隆抗體 109.8 能夠實現 SHC014-MA15 的 50% 中和,但僅在高濃度(10μg/ ml)時(圖2d)。總之,結果表明,針對 SARS-CoV 的廣泛中和抗體可能僅對新興 SARS 樣 CoV 菌株(如 SHC014)具有邊際功效。

圖|SARS-CoV單克隆抗體對SARS樣CoV的療效折線圖 為了評估現有疫苗抵抗 SHC014-MA15 感染的功效,研究人員用雙重滅活的完整 SARS-CoV(DIV)疫苗接種了老年小鼠。先前的工作表明,這種疫苗接種方式可以中和並保護年輕小鼠免受同源病毒的攻擊;然而,該疫苗未能保護其中還觀察到增強的免疫病理的老年動物,這表明由於疫苗接種,動物受到了傷害。在這裡,我們發現 DIV 不能在體重減輕或病毒滴度方面提供 SHC014-MA15 的抗攻擊保護(圖5a,b)。與其他異源組 CoV 的先前報告一致。此外,來自接種 DIV 的老年小鼠的血清也未能中和 SHC014-MA15(如圖5c)。 值得注意的是, DIV 疫苗接種導致了強大的免疫病理和嗜酸性粒細胞增多。這些結果證實,DIV 疫苗不能預防 SHC014 感染,並且可能增加老年接種組的疾病。 與用 DIV 疫苗接種相比,將 SHC014-MA15 用作減毒活疫苗顯示了針對 SARS-CoV 攻擊的潛在交叉保護作用。論文當中的研究人員表示,其用 10 4pfu 的 SHC014-MA15 感染幼鼠,並觀察了 28 天。然後,在第 29 天,他們用 SARS-MA15 攻擊了小鼠。 儘管在 SHC014-MA15 感染後28 天內產生的抗血清,只有極少的 SARS-CoV 中和反應,但先前用高劑量 SHC014-MA15 感染的小鼠可防禦致命劑量的 SARS-MA15 攻擊。 在沒有二級抗原升壓的情況下,28 dpi 表示的抗體滴度的預期峰值,意味着有將隨時間而減少針對 SARS-CoV 的保護。在體重減輕和病毒複製方面,在衰老的 BALb/c 小鼠中觀察到了類似的結果,表明用致死劑量的SARS-CoV攻擊具有保護作用。然而,在某些老年動物中,SHC014-MA1 5感染劑量為 10 4pfu,導致體重減輕和致死率> 10%。 研究人員發現,以較低劑量的 SHC014-MA15(100 pfu)進行疫苗接種不會誘導體重減輕,但也無法保護老年動物免受 SARS-MA15 致命劑量的攻擊。總之言之,根據論文的說法,數據表明,SHC014-MA15 攻擊可能通過保守的表位賦予針對 SARS-CoV 的交叉保護作用,但所需劑量可誘發發病機理,並不能用作減毒疫苗。 確定 SHC014 尖峰具有介導人類細胞感染並引起小鼠疾病的能力後,我們接下來基於用於SARS-CoV的方法合成了全長SHC014-CoV感染性克隆。在Vero細胞中複製顯示SHC014-CoV相對於SARS-CoV沒有缺陷;然而,在感染後24小時和48小時,原代HAE培養物中SHC014-CoV顯着減弱(P<0.01)。 與SARS-CoV Urbani相比,小鼠的體內感染沒有顯示出明顯的體重減輕,但在全長SHC014-CoV感染的肺部顯示出病毒複製減少。總之,這些結果確定了全長SHC014-CoV的生存力,但表明其複製必須與人類呼吸道細胞和小鼠中流行的SARS-CoV的複製相一致,需要進一步的適應。

圖|SHC014-CoV在人呼吸道中複製,但缺乏流行性SARS-CoV的毒力 在 SARS 冠狀病毒流行期間,人們很快發現了棕櫚科動物和人類冠狀病毒之間的聯繫。基於這一發現,有兩種不同觀點範例表述。其中,第一種觀點認為,流行性 SARS-CoV 起源於蝙蝠病毒,躍遷至小窩並在受體結合域(RBD)內引入了變化,以改善與麝貓 Ace2 的結合,隨後在活畜市場上接觸人,使人感染了麝香毒株,而該麝香毒株又適合成為流行毒株。 但是,根據發育周期以及數據分析表明,早期人類SARS菌株與蝙蝠菌株的關係似乎比靈貓菌株更為緊密。因此,第二種觀點認為蝙蝠直接傳播導致SARS-CoV的出現,而棕櫚科動物則是繼發宿主和持續感染的宿主。對於這兩種範例,都認為必須在二級宿主中適應峰值,因為大多數突變預計會在RBD內發生,從而有助於改善感染。兩種理論都暗示蝙蝠冠狀病毒的庫是有限的,宿主範圍的突變既是隨機的又是罕見的,從而降低了人類未來出現突發事件的可能性。

圖|冠狀病毒的出現(傳播)範例 儘管Nature論文表示,這一新的研究,並未打破上述說法與範例,但也的確提出了第三種範式,這一論文的作者團隊認為,蝙蝠 CoV 病毒細胞為了保持“平衡”的刺突蛋白,能夠在不突變的情況下感染人類。通過在SARS-CoV主鏈中包含SHC014刺突的嵌合病毒在人氣道培養物中和在沒有RBD適應的小鼠中引起強烈感染的能力可以說明這一假設。 加上以前鑑定的致病冠狀病毒主鏈的觀察,上述論文研究結果表明,SARS 樣菌株所急需的原材料目前正在動物水庫中流通。值得注意的是,儘管全長SHC014-CoV可能需要額外的骨架適應性來介導人類疾病,但有記錄的CoV家族中的高頻重組事件強調了未來出現的可能性和進一步準備的必要性。 迄今為止,動物種群的基因組學篩選已主要用於鑑定暴發環境中的新型病毒。這裡的方法將這些數據集擴展為檢查病毒出現和治療功效的問題。我們認為,具有SHC014尖峰的病毒由於其在原代人類氣道培養物中複製的能力而成為潛在的威脅,這是人類疾病的最佳可用模型。另外,在小鼠中觀察到的發病機制表明含有SHC014的病毒能夠在沒有RBD適應的情況下在哺乳動物模型中引起疾病。 值得注意的是,相對於SARS-CoV Urbani,與SARS-MA15相比,肺中的向異性和HAE培養物中全長SHC014-CoV的衰減相對於SARS-CoV Urbani而言,提示了ACE2結合以外的因素-包括穗突性,受體生物利用度或拮抗宿主免疫反應中的一部分可能有助於出現。然而,需要對非人類靈長類動物進行進一步測試,以將這些發現轉化為人類致病潛能。重要的是,現有治療方法的失敗定義了進一步研究和開發治療方法的關鍵需求。有了這些知識,就可以產生監視程序,診斷試劑和有效的治療方法,從而防止出現組別特異性CoV,例如SHC014,並且可以將其應用於維護相似異質庫的其他CoV分支。 在以前出現的模型的基礎上,研究人員認為,新型冠狀病毒並沒有增強致病性。作者表示,預計不會產生嵌合病毒(例如SHC014-MA15)會增加致病性的情況。雖然SHC014-MA15相對於其親本小鼠適應的SARS-CoV減毒,但類似的研究檢查了MA15骨架內野生型Urbani尖峰的CoV的致病性,顯示小鼠無體重減輕,病毒複製減少。因此,相對於Urbani峰值–MA15 CoV,SHC014-MA15的發病機理有所改善。 基於這些發現,科學評論小組可能認為類似的研究基於無法冒險進行的循環株構建嵌合病毒,因為不能排除哺乳動物模型中致病性的增加。再加上對小鼠適應株的限制以及使用逃逸突變體開發單克隆抗體的研究,對CoV出現和治療功效的研究可能會嚴重受限。這些數據和限制加在一起,代表了新冠病毒研究關注的十字路口。在制定前進的政策時,必須權衡準備和緩解未來爆發的潛力與創造更多危險病原體的風險。 總體而言,研究人員利用實驗和分析,對已使用宏基因組學數據來識別由循環蝙蝠SARS狀CoV SHC014構成的潛在威脅。由於嵌合的SHC014病毒在人氣道培養物中複製的能力,在體內引起發病機理並逃避當前的治療方法,因此需要針對循環的SARS樣病毒的監視和改進的治療方法。我們的方法還可以利用宏基因組學數據來預測病毒的出現,並將這些知識應用於準備治療未來出現的病毒感染。 培養並製造出新冠病毒的實驗過程以下是鈦媒體編輯整理了上述論文中科學家們培養並製造出一種新型冠狀病毒的實驗過程,這一過程被稱為“病毒,細胞,體外感染和噬菌斑測定方案”。 科學家將從美國陸軍傳染病研究所獲得的野生型 SARS-CoV(Urbani),適應小鼠的 SARS-CoV(MA15)和嵌合型 SARS 型 CoV 病毒細胞在 Vero E6 培養基細胞上。據悉,這一細胞是根據美國病毒學家杜爾貝科(Dulbecco,Renato) 所研製出改良的 Eagle's 培養基上生長。 另外,獲得到的病毒細胞組織,是通過之前研究的信息進行的,其中包括表達 ACE2 直向同源物的 DBT 細胞(Baric實驗室,來源未知),這些都在先前被描述為人類和麝貓感染的細胞組織,ACE2 序列是基於從菊頭蝠,就是蝙蝠 DBT 細胞當中提取,並從中建立新的病毒培養。 作者表示,這一實驗本身是偽型實驗過程,與使用基於 HIV 的偽病毒實驗類似,先前使用武漢病毒研究所提供的 ACE2 直系表達的同源物種的 HeLa 細胞進行檢查,HeLa 細胞在最低必需培養基補充有 10% FCS(Gibco公司,CA)以及 MEM(Gibco公司,CA)中生長,得出下圖在Vero E6,DBT,將Calu-3和2B4原代人呼吸道上皮細胞的生長曲線。 實驗物,也就是仿製的肺,則是在北卡羅來納大學機構審查委員會批准下採購的,而這種肺並不是活體的肺,是在 HAE 培養的人肺。該 HAE 培養物代表高度分化的人氣道上皮,其中包含纖毛和非纖毛上皮細胞以及杯狀細胞,培養物應在氣液界面上生長數周,才拿到該實驗當中。 而後,將細胞用 PBS 溶液進行洗滌,並用病毒接種或在 37℃ 的 PBS 溶液中模擬稀釋 40 分鐘。將細胞洗滌 3 次,並加入新鮮培養基以表示時間 “0”。在每個所述的時間點收穫三個或更多的生物重複樣品,所有病毒的培養均在生物安全級別(BSL)為 3 級的實驗室中進行。 人員和環境方面,將冗餘的生物細胞放進對應的安全櫃中,並有電扇進行散熱。所有人員都穿着特別的衛生強化防護服,為了實驗過程的健康,相關科研人員使用 3M 電動呼吸器(Breathe Easy,3M)進行呼吸,並嚴格佩戴雙手套,使得實驗在安全狀況下進行。 序列聚類和結構建模 實驗中,從 Genbank 或 Pathosystems 資源整合中心(PATRIC)下載具有代表性的 CoV S1 結構域的全長基因組序列和氨基酸序列,並與 ClustalX 進行比對,通過系統分析使用 100 個自舉法或使用 PhyML(https://code.google.com/p/phyml/)封裝。 事實上,這一過程主要是將數據進行比對,對病毒的未來變異進行管控,形成一定的數據模型。 接着,科研人員使用 PhyML 軟件包生成最大可能性數值樹。比例尺代表核苷酸取代。僅標記引導程序支持高於 70% 的節點。該樹顯示 CoV 分為三個不同的系統發育組,分別定義為 α-CoV,β-CoV 和 γ-CoV。對 於β-CoV,經典子群群集標記為 2a,2b,2c 和 2d,對於 α-CoV,標記為 1a 和 1b。使用 Modeller(Max Planck Institute Bioinformatics Toolkit)生成結構模型,以基於晶體結構 2AJF(蛋白質數據庫)生成 SARS RBD 的 SHC014 和 Rs3367 與 ACE2 的同源性模型。在 MacPyMol(1.3版)中可視化和操作同源模型。 SARS樣嵌合病毒的構建 如前所述,野生型和嵌合病毒均來自 SARS-CoV Urbani 或相應的小鼠適應性(SARS-CoV MA15)感染性克隆(ic)病毒細胞。通過提取含有 SHC014 刺突序列的質粒,並連接到 MA15 感染性克隆的 E 和 F 質粒中。設計該克隆並從 Bio Basic 購買六種連續 cDNA,並使用側接獨特的 II 類限制性核酸內切酶位點(BglI)的公開序列。 之後,研究人員對其擴增,切除,連接和純化含有野生型,嵌合 SARS-CoV 和 SHC014-CoV 基因組片段的質粒。然後進行體外轉錄反應以合成全長基因組 RNA,如先前所述將其轉染到 Vero E6 細胞中。收穫轉染細胞的培養基,並用作後續實驗的種子庫。在用於這些研究之前,通過序列分析證實了嵌合和全長病毒。嵌合突變體和全長 SHC014-CoV 的合成構建,這一新的 SARS樣嵌合病毒標準,需要得到北卡羅萊納大學機構生物安全委員會和關注雙重用途研究委員會的批准。 小鼠體內感染 事實上,這份實驗需要根據人體,來了解抵抗力以及病毒形成活動,多數據下,形成小鼠體內感染的數據分析。 論文中稱,其從 Harlan Laboratories 訂購了雌性、10 周齡和 12 個月大的 BALb/c 白變種實驗室老鼠。將動物帶入 BSL3 實驗室,並使其在感染前適應 1 周。對於感染和減毒活疫苗接種,將用氯胺酮和甲苯噻嗪的混合物對小鼠進行麻醉,並在鼻腔感染時用 50μl 磷酸鹽緩衝液(PBS)或稀釋的病毒經鼻內感染,每個時間點,每隻三或四隻小鼠,感染組每劑量都按照條件定量。對於個別小鼠,研究人員可以酌情決定是否將小鼠數據排除在外,包括不吸入全部劑量,鼻腔冒泡或通過口部感染引起的感染。 感染後,在任何動物實驗中均未使用致盲法,且動物未隨機分組。對小鼠進行接種疫苗,通過足墊注射為年輕和老年小鼠接種 20μl 的含明礬或模擬 PBS 的 0.2μg 雙滅活 SARS-CoV 疫苗;然後在 22 天后以相同的方案加強小鼠免疫體質。對於所有組,按照實驗方案,在實驗過程中每天監測動物的疾病臨床體徵(駝背,毛皮鬆動和活動減少)。在頭 7 天裡,每天監測體重是否減輕,此後繼續進行體重監測,直到動物恢復至初始初始體重或連續 3 天顯示體重增加為止。所有體重下降超過其初始體重 20% 的小鼠都被餵食並每天監測多次,只要它們處於 20% 的臨界值以下即可。 按照實驗方案,立即處死體重超過其初始體重 30% 的小鼠。根據研究人員的說法,任何被認為垂死,或不太可能恢復的小鼠,將使用異氟烷過量進行安樂死,並通過頸脫位確認死亡,這種處理方式使用 UNC 機構動物護理和使用委員會(IACUC)批準的方案。 組織學分析 在實驗結束後,取出左肺,浸沒在 10% 福爾馬林緩衝液(Fisher)中,不充氣 1 周。將組織包埋在石蠟中,並由 UNC Lineberger 綜合癌症中心組織病理學核心設施製備 5μm 切片。為了確定抗原染色的程度,使用市售的多克隆 SARS-CoV 抗核衣殼抗體(Imgenex)對切片進行病毒抗原染色,並以盲法方式對氣道和實質進行染色,使用帶有 Olympus DP71 相機的 Olympus BX41 顯微鏡捕獲圖像。 病毒中和測定和統計分析 在這一部分當中,噬斑減少中和效價測定法與先前表徵針對 SARS-CoV 的抗體進行。簡而言之,就是中和抗體或血清,並將其進行兩次連續稀釋,與 100pfu 不同感染性克隆 SARS-CoV 菌株在 37°C 溫度下孵育 1 小時。然後將病毒和抗體以 5×10 5 孔 Vero E6 細胞添加到另一孔板中,並重複多次(n≥2)。 在 37°C 下孵育 1 小時後,研究人員需要在培養基中鋪上 3 ml 0.8% 瓊脂糖。在將板在 37℃ 下孵育 2 天,用中性紅染色 3 小時並計數噬菌斑。計算噬菌斑減少的百分比為(1-((帶有抗體的噬菌斑數量/沒有抗體的噬菌斑數量))×100。 實驗結束後進行統計分析,所有實驗均與兩個實驗組(兩種病毒,或已接種和未接種的隊列)進行對比。因此,病毒的顯著差異是通過在各個時間點進行檢驗確定的。最終的數據以正態分布,在每個比較的組別中,放置出相似的方差。(本文首發鈦媒體App) 原論文地址: https://www.nature.com/articles/nm.3985#auth-14 參考來源: https://microbiology.utmb.edu/faculty/vineet-d-menachery-phd https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/lab-made-coronavirus-triggers-debate-34502 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00262-7

實驗室里人工合成製造培養 的冠狀病毒引發巨大爭議

Ralph Baric, an infectious-disease researcher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, last week (November 9) published a study on his team’s efforts to engineer a virus with the surface protein of the SHC014 coronavirus, found in horseshoe bats in China, and the backbone of one that causes human-like severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in mice. The hybrid virus could infect human airway cells and caused disease in mice, according to the team’s results, which were published in Nature Medicine. The results demonstrate the ability of the SHC014 surface protein to bind and infect human cells, validating concerns that this virus—or other coronaviruses found in bat species—may be capable of making the leap to people without first evolving in an intermediate host, Nature reported. They also reignite a debate about whether that information justifies the risk of such work, known as gain-of-function research. “If the [new] virus escaped, nobody could predict the trajectory,” Simon Wain-Hobson, a virologist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, told Nature. In October 2013, the US government put a stop to all federal funding for gain-of-function studies, with particular concern rising about influenza, SARS, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). “NIH [National Institutes of Health] has funded such studies because they help define the fundamental nature of human-pathogen interactions, enable the assessment of the pandemic potential of emerging infectious agents, and inform public health and preparedness efforts,” NIH Director Francis Collins said in a statement at the time. “These studies, however, also entail biosafety and biosecurity risks, which need to be understood better.” Baric’s study on the SHC014-chimeric coronavirus began before the moratorium was announced, and the NIH allowed it to proceed during a review process, which eventually led to the conclusion that the work did not fall under the new restrictions, Baric told Nature. But some researchers, like Wain-Hobson, disagree with that decision. The debate comes down to how informative the results are. “The only impact of this work is the creation, in a lab, of a new, non-natural risk,” Richard Ebright, a molecular biologist and biodefence expert at Rutgers University, told Nature. But Baric and others argued the study’s importance. “[The results] move this virus from a candidate emerging pathogen to a clear and present danger,” Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, which samples viruses from animals and people in emerging-diseases hotspots across the globe, told Nature.

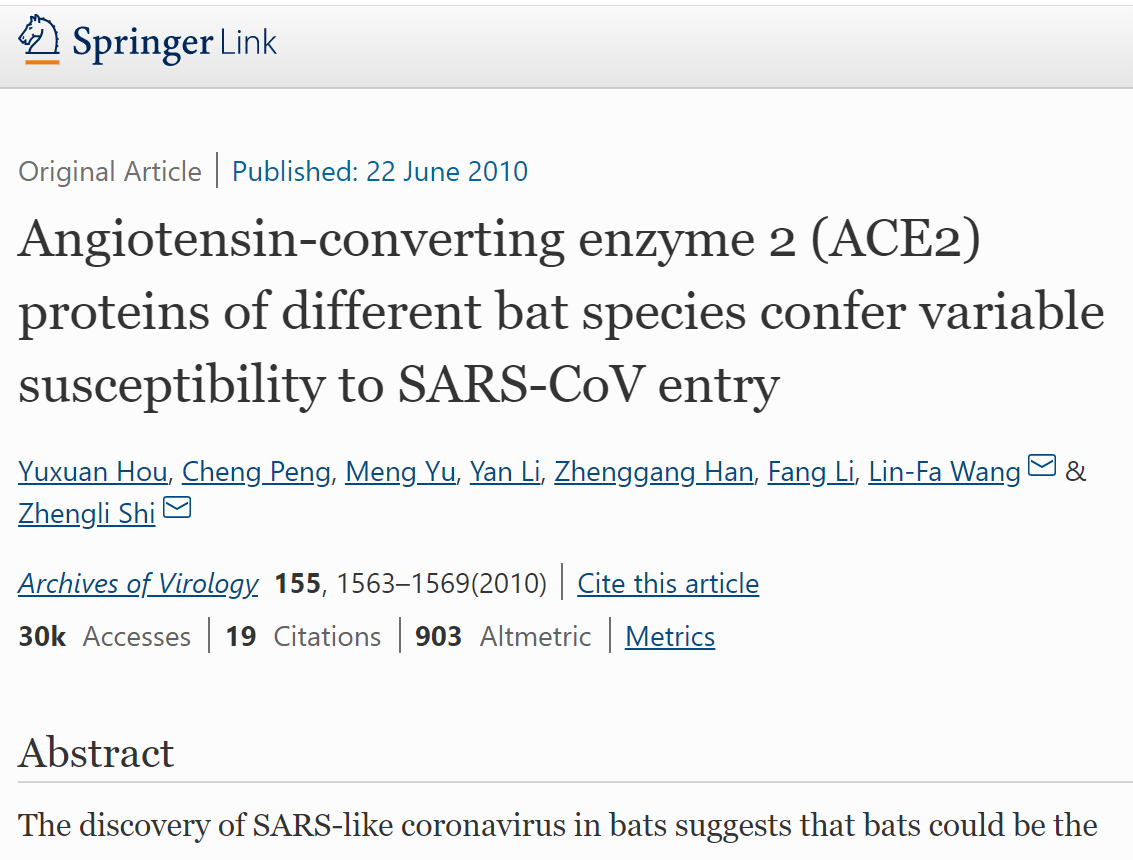

In all, 2019-nCoV has nearly 29,000 nucleotides bases that hold the genetic instruction book to produce the virus. Although it’s one of the many viruses whose genes are in the form of RNA, scientists convert the viral genome into DNA, with bases known in shorthand as A, T, C, and G, to make it easier to study. Many analyses of 2019-nCoV’s sequences have already appeared on virological.org, nextstrain.org, preprint servers like bioRxiv, and even in peer-reviewed journals. The sharing of the sequences by Chinese researchers allowed public health labs around the world to develop their own diagnostics for the virus, which now has been found in 18 other countries. (Science's news stories on the outbreak can be found here.) When the first 2019-nCoV sequence became available, researchers placed it on a family tree of known coronaviruses—which are abundant and infect many species—and found that it was most closely related to relatives found in bats. A team led by Shi Zheng-Li, a coronavirus specialist at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, reported on 23 January on bioRxiv that 2019-nCoV’s sequence was 96.2% similar to a bat virus and had 79.5% similarity to the coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), a disease whose initial outbreak was also in China more than 15 years ago. But the SARS coronavirus has a similarly close relationship to bat viruses, and sequence data make a powerful case that it jumped into people from a coronavirus in civets that differed from human SARS viruses by as few as 10 nucleotides. That’s one reason why many scientists suspect there’s an “intermediary” host species—or several—between bats and 2019-nCoV. According to Bedford’s analysis, the bat coronavirus sequence that Shi Zheng-Li’s team highlighted, dubbed RaTG13, differs from 2019-nCoV by nearly 1100 nucleotides. On nextstrain.org, a site he co-founded, Bedford has created coronavirus family trees (example below) that include bat, civet, SARS, and 2019-nCoV sequences. (The trees are interactive—by dragging a computer mouse over them, it’s easy to see the differences and similarities between the sequences.)

Bedford’s analyses of RaTG13 and 2019-nCoV suggest that the two viruses shared a common ancestor 25 to 65 years ago, an estimate he arrived at by combining the difference in nucleotides between the viruses with the presumed rates of mutation in other coronaviruses. So it likely took decades for RaTG13-like viruses to mutate into 2019-nCoV. Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), another human disease caused by a coronavirus, similarly has a link to bat viruses. But studies have built a compelling case it jumped to humans from camels. And the phylogenetic tree from Shi’s bioRxiv paper (below) makes the camel-MERS link easy to see.

The longer a virus circulates in a human populations, the more time it has to develop mutations that differentiate strains in infected people, and given that the 2019-nCoV sequences analyzed to date differ from each other by seven nucleotides at most, this suggests it jumped into humans very recently. But it remains a mystery which animal spread the virus to humans. “There’s a very large gray area between viruses detected in bats and the virus now isolated in humans,” says Vincent Munster, a virologist at the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases who studies coronaviruses in bats, camels, and others species. Strong evidence suggests the marketplace played an early role in spreading 2019-nCoV, but whether it was the origin of the outbreak remains uncertain. Many of the initially confirmed 2019-nCoV cases—27 of the first 41 in one report, 26 of 47 in another—were connected to the Wuhan market, but up to 45%, including the earliest handful, were not. This raises the possibility that the initial jump into people happened elsewhere. According to Xinhua, the state-run news agency, “environmental sampling” of the Wuhan seafood market has found evidence of 2019-nCoV. Of the 585 samples tested, 33 were positive for 2019-nCoV and all were in the huge market’s western portion, which is where wildlife were sold. “The positive tests from the wet market are hugely important,” says Edward Holmes, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Sydney who collaborated with the first group to publicly release a 2019-nCoV sequence. “Such a high rate of positive tests would strongly imply that animals in the market played a key role in the emergence of the virus.” Yet there have been no preprints or official scientific reports on the sampling, so it’s not clear which, if any, animals tested positive. “Until you consistently isolate the virus out of a single species, it’s really, really difficult to try and determine what the natural host is,” says Kristian Andersen, an evolutionary biologist at Scripps Research. One possible explanation for the confusion about where the virus first entered humans is if there was a batch of recently infected animals sold at different marketplaces. Or an infected animal trader could have transmitted the virus to different people at different markets. Or, Bedford suggests, those early cases could have been infected by viruses that didn’t easily transmit and sputtered out. “It would be hugely helpful to have just a sequence or two from the marketplace [environmental sampling] that could illuminate how many zoonoses occurred and when they occurred,” Bedford says.

A research group sent fecal and other bodily samples from bats they trapped in caves to the Wuhan Institute of Virology to search for coronaviruses.

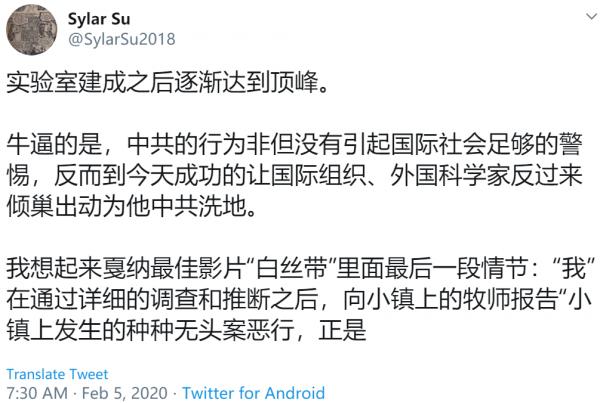

ECOHEALTH ALLIANCE In the absence of clear conclusions about the outbreak’s origin, theories thrive, and some have been scientifically shaky. A sequence analysis led by Wei Ji of Peking University and published online by the Journal of Medical Virology received substantial press coverage when it suggested that “snake is the most probable wildlife animal reservoir for the 2019 CoV.” Sequence specialists, however, pilloried it. Conspiracy theories also abound. A CBC News report about the Canadian government deporting Chinese scientists who worked in a Winnipeg lab that studies dangerous pathogens was distorted on social media to suggest that they were spies who had smuggled out coronaviruses. The Wuhan Institute of Virology, which is the premier lab in China that studies bat and human coronaviruses, has also come under fire. “Experts debunk fringe theory linking China’s coronavirus to weapons research,” read a headline on a story in The Washington Post that focused on the facility. Concerns about the institute predate this outbreak. Nature ran a story in 2017 about it building a new biosafety level 4 lab and included molecular biologist Richard Ebright of Rutgers University, Piscataway, expressing concerns about accidental infections, which he noted repeatedly happened with lab workers handling SARS in Beijing. Ebright, who has a long history of raising red flags about studies with dangerous pathogens, also in 2015 criticized an experiment in which modifications were made to a SARS-like virus circulating in Chinese bats to see whether it had the potential to cause disease in humans. Earlier this week, Ebright questioned the accuracy of Bedford’s calculation that there are at least 25 years of evolutionary distance between RaTG13—the virus held in the Wuhan virology institute—and 2019-nCoV, arguing that the mutation rate may have been different as it passed through different hosts before humans. Ebright tells ScienceInsider that the 2019-nCoV data are “consistent with entry into the human population as either a natural accident or a laboratory accident.”

Shi did not reply to emails from Science, but her longtime collaborator, disease ecologist Peter Daszak of the EcoHealth Alliance, dismissed Ebright’s conjecture. “Every time there’s an emerging disease, a new virus, the same story comes out: This is a spillover or the release of an agent or a bioengineered virus,” Daszak says. “It’s just a shame. It seems humans can’t resist controversy and these myths, yet it’s staring us right in the face. There’s this incredible diversity of viruses in wildlife and we’ve just scratched the surface. Within that diversity, there will be some that can infect people and within that group will be some that cause illness.”

A team of researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology and the EcoHealth Alliance have trapped bats in caves all over China, like this one in Guangdong, to sample them for coronaviruses.

ECOHEALTH ALLIANCE Daszak and Shi’s group have for 8 years been trapping bats in caves around China to sample their feces and blood for viruses. He says they have sampled more than 10,000 bats and 2000 other species. They have found some 500 novel coronaviruses, about 50 of which fall relatively close to the SARS virus on the family tree, including RaTG13—it was fished out of a bat fecal sample they collected in 2013 from a cave in Moglang in Yunnan province. “We cannot assume that just because this virus from Yunnan has high sequence identity with the new one that that’s the origin,” Daszak says, noting that only a tiny fraction of coronaviruses that infect bats have been discovered. “I expect that once we’ve sampled and sampled and sampled across southern China and central China that we’re going to find many other viruses and some of them will be closer [to 2019-nCoV].” It’s not just a “curious interest” to figure out what sparked the current outbreak, Daszak says. “If we don't find the origin, it could still be a raging infection at a farm somewhere, and once this outbreak dies, there could be a continued spillover that’s really hard to stop. But the jury is still out on what the real origins of this are.” ———— The End ————

|

|

|

|

|

| 實用資訊 | |

|

|

| 一周點擊熱帖 | 更多>> |

| 一周回復熱帖 |

| 歷史上的今天:回復熱帖 |

| 2019: | 一件衣服9999元不貴啊 | |

| 2019: | 不給自己小孩打疫苗的都是有錢,有學問 | |

| 2018: | 今後一切單位都要建立黨委,包括外企, | |

| 2018: | 對台灣要促統,對台灣百姓可能發身份證 | |

| 2017: | 建議把總統令不能暫時阻止的難民送到第 | |

| 2017: | 為什麼美國政府雇員多為民主黨擁躉? | |

| 2016: | 為了咱們勞動人民的血汗不被官府榨乾, | |

| 2016: | 雪山下的絳珠草:暴徒和警察,香港之夜 | |

| 2015: | 昨晚嚇死俺廖。 | |

| 2015: | 看了阿潤的帖我也覺得國內現在醫保很不 | |