| 百度真戰友衛星照遮蓋圖告你集中營位置 |

| 送交者: Pascal 2020年08月27日13:37:59 於 [五 味 齋] 發送悄悄話 |

|

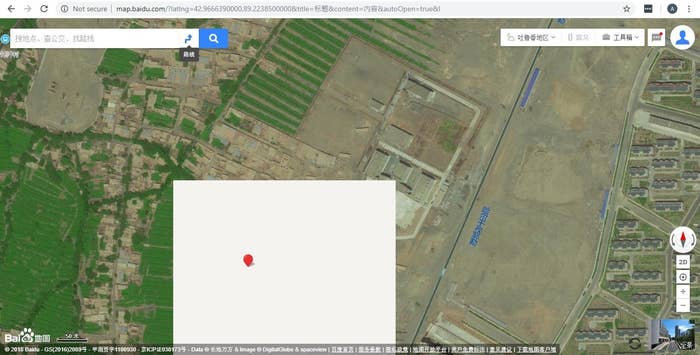

Baidu / Via map.baidu.com A masked tile on Baidu Maps. This project was supported by the Open Technology Fund, the Pulitzer Center, and the Eyebeam Center for the Future of Journalism. In the summer of 2018, as it became even harder for journalists to work effectively in Xinjiang, a far-western region of China, we started to look at how we could use satellite imagery to investigate the camps where Uighurs and other Muslim minorities were being detained. At the time we began, it was believed that there were around 1,200 camps in existence, while only several dozen had been found. We wanted to try to find the rest.

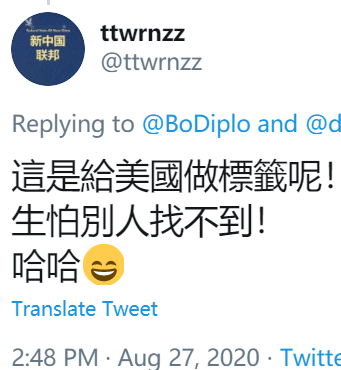

機翻譯文: 該項目得到了開放技術基金,普利策中心和Eyebeam新聞未來中心的支持。 在2018年夏季,由於記者在中國偏遠地區新疆的有效工作變得更加困難,我們開始研究如何使用衛星圖像來調查維吾爾人和其他穆斯林少數民族正在紮營的營地被拘留。在我們開始的時候,據信大約有1200個難民營,而僅發現了幾十個。我們想找到其餘的。 當我們注意到使用中國製圖平台百度地圖時,在一個已知營地附近加載衛星圖像圖塊時遇到了某種問題,這是我們取得的突破。衛星圖像較舊,但縮小時還算不錯-但在某一點上,營地上方會出現淺灰色的平鋪瓷磚。當您進一步放大時,它們消失了,而衛星圖像被標準的灰色參考圖塊所代替,該圖塊顯示了建築物輪廓和道路等特徵。 當時,百度在新疆大部分地區只有中等分辨率的衛星圖像,當您拉近時,將由其一般參考地圖圖塊取代。那不是這裡發生的事情-營地位置的這些淺灰色瓷磚與參考地圖瓷磚的顏色不同,並且缺少任何繪製的信息,例如道路。我們還知道,這並不是加載圖塊或地圖中缺少的信息的失敗。通常,當地圖平台無法顯示圖塊時,它會提供帶有水印的標準空白圖塊。這些空白瓷磚的顏色也比我們在營地上注意到的瓷磚要深。 一旦發現可以可靠地複製空白圖塊現象,我們便開始查看其他營地,這些營地的位置已經為公眾所知,以查看是否可以觀察到那裡發生的同一件事。劇透:我們可以。在我們的可行性研究中使用的六個營地中,五個營地在百度第18縮放級別的位置上有空白圖塊,僅在此縮放級別上出現,而在您進一步放大時消失。六個營地中的一個沒有空白地磚-一位在2019年訪問了該地點的人說該地點已經關閉,這很可能可以解釋出來。但是,我們後來發現,空白磚並沒有在市中心使用,而只是在城市邊緣和更多農村地區使用。(百度未回應重複的置評請求。) 確定我們可以以這種方式找到實習營地之後,我們檢查了整個新疆的百度衛星圖塊,包括空白的遮蓋圖塊,這些圖塊在地圖上形成了單獨的圖層。我們通過將被遮罩的位置與Google Earth,歐洲航天局的Sentinel Hub和Planet Labs的最新圖像進行比較,從而分析了被遮罩的位置。 整個新疆總共有500萬個蒙面磚。它們似乎涵蓋了具有戰略意義的任何領域,包括軍事基地和訓練場,監獄,發電廠,還包括礦山以及一些商業和工業設施。我們有太多的地方無法分類,因此我們通過重點關注城鎮和主要道路周圍的區域來縮小範圍。 監獄和拘留所必須在基礎設施附近,對於初學者來說,您需要在那裡購買大量建築材料和重型機械。中國當局還需要良好的道路和鐵路,以將成千上萬的新拘留者帶到那裡,就像在大規模拘留運動的頭幾個月那樣。因此,分析主要基礎設施附近的位置是重點關注我們最初的搜索的一個好方法。這使我們有大約50,000個位置可供查看。 我們開始使用為支持調查和幫助管理數據而構建的自定義Web工具,系統地對蒙版塊的位置進行分類。我們以這種方式分析了新疆南部的維吾爾人心臟地帶喀什地區以及鄰近的克孜勒蘇地區的一部分。在查看了10,000個口罩瓷磚的位置並確定了多個帶有拘留中心,監獄和營地標誌的設施之後,我們對這些設施的設計範圍以及它們可能用於的地點的種類有了一個很好的認識。被發現。 我們很快開始注意到與早期已知的難民營相比,這些地方有多大,以及它們的證券化程度有多大。在場地布局,建築和安全方面,與新疆較早形成的營地改建後的學校和醫院相比,它們與中國其他監獄更相似。新型化合物還可以持久使用,而早期的轉換則沒有。例如,外圍牆是用厚混凝土製成的,比起早期營地的鐵絲網圍欄要花費更長的時間才能建造甚至可能要拆除。 在幾乎每個縣,我們發現帶有拘留中心標誌的建築物,以及具有大型,高安全性營地和/或監獄的新設施。通常,在鎮中心有一個較舊的拘留中心,而在郊區則有一個新的營地和監獄,通常是在最近開發的工業區。在我們尚未在給定縣找到這些設施的地方,這種模式促使我們繼續尋找,特別是在最近沒有衛星圖像的地區。在沒有公共高分辨率圖像的地方,我們使用了Planet Labs和Sentinel的中等分辨率圖像來定位可能的站點。 這是Google Earth中最新發布的高分辨率圖像中的哈密縣義烏。這張照片攝於2006年。白色標記顯示的是一棟現已拆除的舊監獄,紅色標記顯示的是郊區的新監獄。

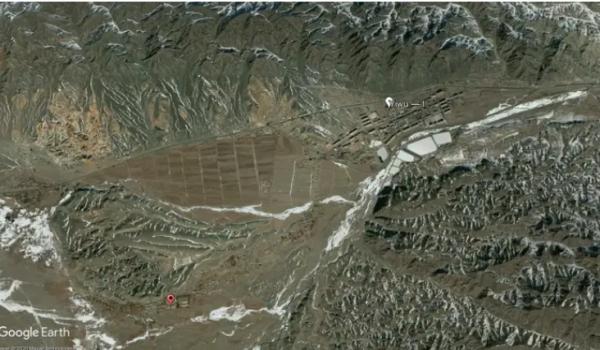

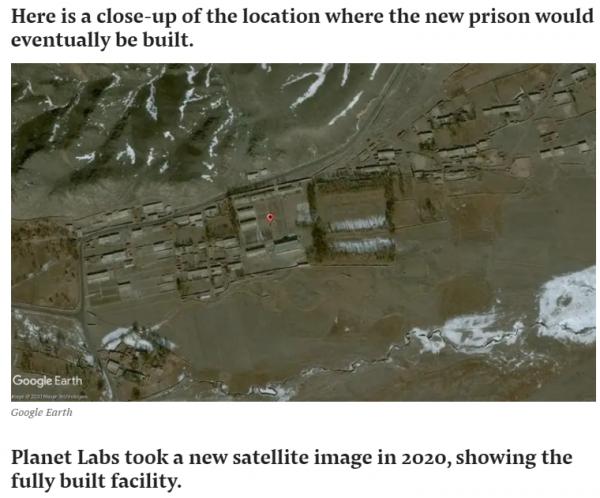

谷歌地球 這是最終建造新監獄的地點的特寫鏡頭。谷歌地球 Planet Labs在2020年拍攝了一張新的衛星圖像,顯示了完整的設施。

監獄要求-為什麼將監獄建在原地

這些地方在城鎮附近發展是有充分的理由的。偶爾會有一個較偏僻的營地,例如在大坂城的龐大的拘留所,但即使在那兒,它也毗鄰一條主要道路,附近有一個小鎮。原則上,使監獄或營地靠近現有城鎮可以最大程度地減少被拘留者必須被運送的距離(儘管還有一些例子表明,從喀什到庫爾勒,整個新疆都被俘虜和被拘留者,整個無人機視頻都重新出現了)據分析師稱,最近)。對於家庭來說,探望被關押的親人更容易。靠近城鎮意味着可以更輕鬆地為監獄或營地配備人員。警衛有家庭,他們的孩子需要上學,其伴侶有工作,需要醫療保健,等等。首先需要建築工人建造監獄。對於便利設施也很有用。監獄和營地需要電力,水和電話線。與將新的管道和電纜鋪設到更遠的地方相比,與現有的附近網絡連接更便宜,更容易。 最後,您需要用於監獄的大塊土地,最好在將來有擴展的空間,這就是最近開發的工業區所提供的:服務完善的大塊土地,靠近現有城鎮。在工業區建造房屋還使營地靠近工廠以進行強迫勞動。儘管許多難民營的工廠都設有工廠,但在某些情況下,我們知道被拘留者被送往其他工廠工作。 我們的網站清單 我們總共在新疆確定了428個帶有監獄和拘留中心標誌的地點。這些地點中有許多都設有2-3個拘留設施-營地,審前行政拘留中心或監獄。我們打算進一步分析這些位置,並在接下來的幾個月中使我們的數據庫更加精細。 在這些地點中,我們認為有315個被用作當前拘留計劃的一部分-268個新的營地或監獄綜合體,以及47個在過去四年中沒有擴大的審前行政拘留中心。我們有目擊者的證詞表明,這些拘留中心經常被用來拘留人員,然後這些人經常被轉移到其他營地,因此,我們認為將它們包括在內很重要。從這315個營地中排除的是我們認為可能已經關閉的39個營地,以及已經關閉的11個營地-要麼它們已被拆除,要麼我們有證詞表明它們已不再使用。其他研究人員還確定了另外14個位置,但我們的團隊只能檢查衛星證據,在這些情況下,這些證據很薄弱。這14個未包含在我們的列表中。 我們還找到了我們認為屬於2016年之前計劃的63所監獄。這些設施通常是在目前的拘留計劃之前建造的,有時甚至是幾十年,並且自2016年以來並未進行大規模擴建。它們的風格也不同於拘留中心(中文稱為“看守所”),以及來自較新的陣營。這些設施不屬於我們認為是當前實習計劃一部分的315設施,而是單獨包含在我們的數據庫中。 許多較早的營地,是從其他用途轉換而來的,通常在2018年末或2019年初拆除了庭院圍欄,watch望塔和其他安全設施。在某些情況下,拆除了大多數路障,以及通常情況下,汽車停在大院中的多個地方,這表明它們已不再是露營地,在我們的數據庫中被歸類為封閉的。在某些情況下,安全設施的拆除與附近較大的,更高安全設施的開放同時進行,這表明被拘留者可能已被轉移到較新的地點。 如果設施是專門為營地建造的,並且已經拆除了庭院圍欄,但在其他方面卻沒有任何用途的變化(例如大院中的汽車),我們認為它們很可能仍是營地-儘管安全級別較低。 致謝 我們的工作還建立在Shawn Zhang,Adrian Zenz,Bitter Winter,Gene Bunin,ETNAM,Open Street Map貢獻者和Laugai手冊等人的工作之上-我們試圖驗證這些數據庫中的所有位置(並嘗試以查找《勞改手冊》中的難民營),將其添加到我們相關的數據庫中,並對其進行分類。澳大利亞戰略政策研究所(ASPI)的工作,尤其是Nathan Ruser及其在該項目早期的建議,也具有無價的價值。我們還要指出與我們合作的口譯人員的貢獻。出於安全原因,我們不會共享姓名或其他標識詳細信息,但還是要公開感謝我們-您知道自己是誰。 艾莉森·基林(Alison Killing)在 開放技術基金會(Open Technology Fund)的贈款和進一步協助下進行了此報告。 Our breakthrough came when we noticed that there was some sort of issue with satellite imagery tiles loading in the vicinity of one of the known camps while using the Chinese mapping platform Baidu Maps. The satellite imagery was old, but otherwise fine when zoomed out — but at a certain point, plain light gray tiles would appear over the camp location. They disappeared as you zoomed in further, while the satellite imagery was replaced by the standard gray reference tiles, which showed features such as building outlines and roads. At that time, Baidu only had satellite imagery at medium resolution in most parts of Xinjiang, which would be replaced by their general reference map tiles when you zoomed in closer. That wasn’t what was happening here — these light gray tiles at the camp location were a different color than the reference map tiles and lacked any drawn information, such as roads. We also knew that this wasn’t a failure to load tiles, or information that was missing from the map. Usually when a map platform can’t display a tile, it serves a standard blank tile, which is watermarked. These blank tiles are also a darker color than the tiles we had noticed over the camps. Once we found that we could replicate the blank tile phenomenon reliably, we started to look at other camps whose locations were already known to the public to see if we could observe the same thing happening there. Spoiler: We could. Of the six camps that we used in our feasibility study, five had blank tiles at their location at zoom level 18 in Baidu, appearing only at this zoom level and disappearing as you zoomed in further. One of the six camps didn’t have the blank tiles — a person who had visited the site in 2019 said it had closed, which could well have explained it. However, we later found that the blank tiles weren’t used in city centers, only toward the edge of cities and in more rural areas. (Baidu did not respond to repeated requests for comment.) Having established that we could probably find internment camps in this way, we examined Baidu's satellite tiles for the whole of Xinjiang, including the blank masking tiles, which formed a separate layer on the map. We analyzed the masked locations by comparing them to up-to-date imagery from Google Earth, the European Space Agency’s Sentinel Hub, and Planet Labs. In total there were 5 million masked tiles across Xinjiang. They seemed to cover any area of even the slightest strategic importance — military bases and training grounds, prisons, power plants, but also mines and some commercial and industrial facilities. There were far too many locations for us to sort through, so we narrowed it down by focusing on the areas around cities and towns and major roads. Prisons and internment camps need to be near infrastructure — you need to get large amounts of building materials and heavy machinery there to build them, for starters. Chinese authorities would have also needed good roads and railways to bring newly detained people there by the thousand, as they did in the early months of the mass internment campaign. Analyzing locations near major infrastructure was therefore a good way to focus our initial search. This left us with around 50,000 locations to look at. We began to sort through the mask tile locations systematically using a custom web tool that we built to support our investigation and help manage the data. We analyzed the whole of Kashgar prefecture, the Uighur heartland, which is in the south of Xinjiang, as well as parts of the neighboring prefecture, Kizilsu, in this way. After looking at 10,000 mask tile locations and identifying a number of facilities bearing the hallmarks of detention centers, prisons, and camps, we had a good idea of the range of designs of these facilities and also the sorts of locations in which they were likely to be found. We quickly began to notice how large many of these places are — and how heavily securitized they appear to be, compared to the earlier known camps. In site layout, architecture, and security features, they bear greater resemblance to other prisons across China than to the converted schools and hospitals that formed the earlier camps in Xinjiang. The newer compounds are also built to last, in a way that the earlier conversions weren’t. The perimeter walls are made of thick concrete, for example, which takes much longer to build and perhaps later demolish, than the barbed wire fencing that characterizes the early camps. In almost every county, we found buildings bearing the hallmarks of detention centers, plus new facilities with the characteristics of large, high-security camps and/or prisons. Typically, there would be an older detention center in the middle of the town, while on the outskirts there would be a new camp and prison, often in recently developed industrial areas. Where we hadn’t yet found these facilities in a given county, this pattern pushed us to keep on looking, especially in areas where there was no recent satellite imagery. Where there was no public high-resolution imagery, we used medium-resolution imagery from Planet Labs and Sentinel to locate likely sites. Planet was then kind enough to give us access to high-resolution imagery for these locations and to task a satellite to capture new imagery of some areas that hadn’t been photographed in high resolution since 2006. In one county, this allowed us to see that the detention center that had previously been identified by other researchers had been demolished and to find the new prison just out of town. This is Yiwu, Hami prefecture in Google Earth, in the most recent publicly available high-resolution imagery. The photo was taken in 2006. The white marker shows the old, now-demolished prison and the red marker shows the new one on the outskirts.

Google Earth Here is a close-up of the location where the new prison would eventually be built.Google Earth Planet Labs took a new satellite image in 2020, showing the fully built facility.Planet Labs Prison requirements — why prisons are built where they are There’s good reason why these places are developed close to towns. There’s the occasional camp in a more remote location, such as the sprawling internment camp in Dabancheng, but even there it’s next to a major road, with a small town nearby. Having the prison or camp close to an existing town minimizes, in principle, the distance that detainees must be transported (although there are also examples of prisoners and detainees being taken right across Xinjiang, from Kashgar to Korla, as in the drone video that reemerged recently, according to analysts). It is easier for families to visit loved ones who are in custody. Being near a town means that a prison or camp can be staffed more easily. Guards have families, their children need to go to school, their partners have jobs, they need access to healthcare, etc. Construction workers are needed to build the prison in the first place. It is also useful for amenities. Prisons and camps need electricity, water, telephone lines. It is way cheaper and easier to connect to an existing nearby network than to run new pipes and cables tens of kilometers to a more remote location. Finally, you need a large plot of land for a prison, preferably with space to expand in the future, and this is what the recently developed industrial estates offer: large, serviced plots, close to existing towns and cities. Building in industrial estates also places the camps close to factories for forced labor. While many camps have factories within their compounds, in several cases that we know of detainees are bused to other factory sites to work. Our list of sites In total we identified 428 locations in Xinjiang bearing the hallmarks of prisons and detention centers. Many of these locations contain two to three detention facilities — a camp, pretrial administrative detention center, or prison. We intend to analyze these locations further and make our database more granular over the next few months. Of these locations, we believe 315 are in use as part of the current internment program — 268 new camp or prison complexes, plus 47 pretrial administrative detention centers that have not been expanded over the past four years. We have witness testimony showing that these detention centers have frequently been used to detain people, who are often then moved on to other camps, and so we feel it is important to include them. Excluded from this 315 are 39 camps that we believe are probably closed and 11 that have closed — either they’ve been demolished or we have witness testimony that they are no longer in use. There are a further 14 locations identified by other researchers, but where our team has only been able to check the satellite evidence, which in these cases is weak. These 14 are not included in our list. We have also located 63 prisons that we believe belong to earlier, pre-2016 programs. These facilities were typically built several years — in some cases, several decades — before the current internment program and have not been significantly extended since 2016. They are also different in style from the detention centers, known in Chinese as “kanshousuo,” and also from the newer camps. These facilities are not part of the 315 we believe to be in use as part of the current internment program and are included separately in our database. Many of the earlier camps, which were converted from other uses, had their courtyard fencing, watchtowers, and other security features removed, often in late 2018 or early 2019. In some cases, the removal of most barricading, plus the fact that there are often cars parked in several places across the compounds, suggests that they’re no longer camps and are classified as probably closed in our database. The removal of the security features, in several cases, coincided with the opening of a larger, higher-security facility being completed nearby, suggesting that detainees may have been moved to the newer location. Where facilities were purpose-built as camps and have had courtyard fencing removed but otherwise don’t show any change of use (like cars in the compound), we think they’re likely to still be camps — albeit with lower levels of security. Acknowledgments Our work has also built on the work of others, Shawn Zhang, Adrian Zenz, Bitter Winter, Gene Bunin, ETNAM, Open Street Map contributors, and the Laogai Handbook — we have sought to verify all of the locations in these databases (and attempted to locate the camps in the case of the Laogai Handbook), added them to our database where relevant, and classified them. The work of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), especially Nathan Ruser and his advice at an early stage of this project, was also invaluable. We would also like to note the contribution of the interpreters who worked with us. For security reasons, we aren’t sharing names or other identifying details, but would like nevertheless to publicly extend our thanks — you know who you are. Alison Killing conducted this reporting with a grant and further assistance from the Open Technology Fund. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/alison_killing/satellite-images-investigation-xinjiang-detention-camps

|

|

|

|

|

| 實用資訊 | |

|

|

| 一周點擊熱帖 | 更多>> |

| 一周回復熱帖 |

| 歷史上的今天:回復熱帖 |

| 2019: | 烤死狗開門生意興隆,存貨賣了一大堆人 | |

| 2019: | 中共真是沒眼色,G7英美已經好得穿進一 | |

| 2018: | P2P掘堤崩塌、外企撤離、股市斷崖、消 | |

| 2018: | 川總在貿易上搞1對1談判是完全正確的。 | |

| 2017: | 不說法語 | |

| 2017: | 孔子拜見老子,回來後三天不說話,最後 | |

| 2016: | 史政研究所:被消失的三千萬地主階層 | |

| 2016: | 七月初用老媽的身份證開了個銀行帳戶, | |

| 2015: | 從日本史料看,誰在真正抗日! | |

| 2015: | 國人的墮落也可以從網絡語言反應出來 | |