| 有些中国人身上带有汉奸卖国基因陈竞立 |

| 送交者: Pascal 2019年04月20日12:59:37 于 [五 味 斋] 发送悄悄话 |

|

有些中国人身上带有汉奸卖国贼基因 有些中国人身上带有汉奸卖国贼基因 —— 大外宣宣长东网 网络评论舆情导向员 陈竞立同志 2019-04-20 星期六 11:31:55 http://news.creaders.net/china/2019/04/20/2080653.html

摩根大通集团(英语:JPMorgan Chase, NYSE:JPM, 东证1部除牌 前8634),财经界称“摩通”,总部位于美国纽约市,2017年总资产 25,336亿美元,总存款14,439.82亿美元,[1]商业银行部旗下分行 5100家。[2] 2011年10月,摩根大通的资产规模超越美国银行成为 美国最大的金融服务机构[3]。 摩根大通的业务遍及50多个国家,包括投资银行、金融交易处理、 投资管理、商业金融服务、个人银行等。现时的摩根大通于2000年 由大通曼哈顿银行及J.P.摩根公司合并而成,并于2004年与2008年 分别收购芝加哥第一银行、华盛顿互惠银行、[4]和美国著名投资 银行贝尔斯登。[5]

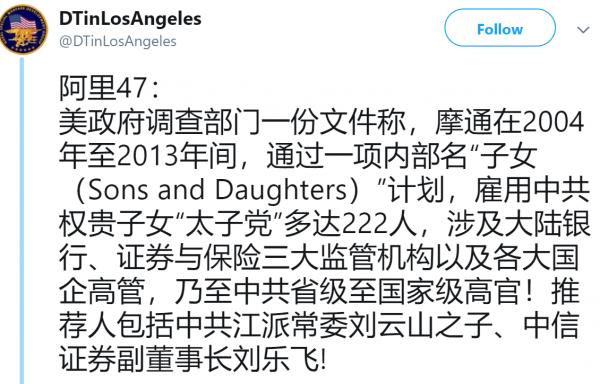

中共中央常委刘云山同志之子刘乐飞 https://twitter.com/DTinLosAngeles/status/1119264205717164032

More 阿里48: 摩根大通尚未受到违法指控。根据《反海外腐败法》,企业行为必须具有“腐败”意图,或者期望能以提供工作机会来换取政府业务,才能被定性为违法。具体到阿里巴巴的情况,其股权掌握在层层空壳公司手中,而这些公司往往在加勒比海的一座座避税天堂中兜兜转转。 (这些人专门研究了美国法律!) https://twitter.com/DTinLosAngeles/status/1119264205717164032 JPMorgan Hiring Put China’s Eliteon an Easy TrackBY JESSICA SILVER-GREENBERG AND BEN PROTESSAUGUST 29, 2013 10:00 PM

The program was originally called “Sons and Daughters.” And although it was supposed to protect JPMorgan Chase’s business dealings in China, the program went so off track that it is now the focus of a federal bribery investigation in the United States, interviews and a confidential government document show. JPMorgan started the program in 2006 as the friends and family of China’s ruling elite were clamoring for jobs at the bank, according to the interviews with former bank employees and financial executives in China and the United States. The program’s existence, which has not been previously reported, suggests that the bank’s hiring of such employees was widespread. Saying they wanted to weed out nepotism and avoid bribery charges in the United States, JPMorgan employees in Asia started the program to hire well-connected candidates on a separate track from ordinary applicants, the employees and executives said. Without the program and its heightened scrutiny of the candidates, the employees argued, JPMorgan might improperly hire the children of Chinese officials to win business. But in the months and years that followed, the two-tiered process that could have prevented questionable hiring practices instead fostered them, according to the interviews as well as the confidential government document. Applicants from prominent Chinese families, interviews show, often faced few job interviews and relaxed standards. While many candidates met or exceeded the bank’s requirements, some had subpar academic records and lacked relevant expertise. JPMorgan, which declined to comment, has not been accused of any wrongdoing. And no one has indicated that the children of Chinese officials helped the bank secure business deals. Furthermore, public documents do not offer a concrete link between the bank’s hiring practices and its ability to secure business deals. Yet, according to the interviews, which were conducted on the condition of anonymity, JPMorgan employees in Asia recognized the benefit of hiring Chinese officials’ children. In an internal document, the employees linked the hires to the “revenue” JPMorgan obtained from companies run by those same officials. It is unclear why and when the “Sons and Daughters” program shifted from a safeguard into a liability. But the results were clear: Children with elite pedigrees faced lower standards. In one instance, according to the interviews, the bank continued to employ the son of Tang Shuangning, the chairman of a state-controlled financial conglomerate, even though some JPMorgan officials questioned the younger Mr. Tang’s financial expertise. The son, whose résumé included impressive stints at other global banks, is one of two former JPMorgan employees to surface in an antibribery investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission, according to the confidential agency document sent to the bank and reviewed by The New York Times. The S.E.C. document — a May 2013 letter to JPMorgan that outlined the scope of the agency’s inquiry — sought “documents sufficient to identify all persons involved in the decision to hire” the employees. The S.E.C. did not inquire about the daughter of Ning Gaoning, the chairman of China’s giant state run food company, Cofco. However, according to a review of securities filings and public records, she was an intern at JPMorgan during the summer of 2012. JPMorgan won business from Cofco, or a subsidiary, before she joined the bank. Yet after she arrived, a subsidiary of Cofco also hired JPMorgan to advise on its plan to raise about $580 million through an issuance of shares, a deal that could draw interest from the S.E.C. The S.E.C. is coordinating its civil investigation with federal prosecutors and the F.B.I., officials said on Thursday, though the criminal authorities have not yet contacted the bank. Hong Kong authorities are also investigating the hiring practices, according to people briefed on the matter. According to the interviews, an internal JPMorgan investigation into its hiring practices across the globe has so far identified more than 250 well-connected hires in Asia alone. That number included the sons and daughters of private Chinese companies, a hiring practice that would not violate United States law but could cause regulatory problems overseas. At the heart of the S.E.C.’s investigation is the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977, which essentially bans United States companies from giving “anything of value” to a foreign official to win “an improper advantage” in retaining business. According to legal experts, there is nothing inherently improper about hiring well-connected people. To run afoul of the law, a company must act with “corrupt” intent, or with the expectation of offering a job in exchange for government business. It is unclear whether the S.E.C. will find such a link in JPMorgan’s case. Still, according to securities filings and the confidential S.E.C. document, some of the bank’s hiring came at an opportune time. One striking example was the hiring of Tang Xiaoning, whose father is the chairman of the China Everbright Group, the state-controlled financial conglomerate. Before the hiring in 2010, the bank’s business with China Everbright was limited, if not nonexistent, based on a review of securities filings and news reports. Since then, though, JPMorgan won a steady flow of business. In 2011, China Everbright’s banking subsidiary picked JPMorgan as one of 12 financial advisers on its decision to become a public company, a common move in China for businesses affiliated with the government. While that deal was delayed amid global economic turmoil and questions about China’s banking system, JPMorgan has since secured other coveted business from China Everbright. In 2012, for example, JPMorgan was the sole bank hired to advise China Everbright International, a subsidiary focused on alternative energy businesses, on a $162 million sale of shares, according to Standard & Poor’s Capital IQ, a research service. JPMorgan also advised the China Everbright Group on its role in what was, according to the research firm Dealogic, the largest-ever private equity deal in China. With those relationships in mind, the S.E.C. asked the bank for “all documents” relating to the younger Mr. Tang’s “recruitment, hiring” and application. The S.E.C. is also examining the hiring of Zhang Xixi, whose father is Zhang Shuguang, the former deputy chief engineer of China’s railway ministry. She joined JPMorgan around 2007. In the months and years to come, the bank nestled closer to the railways business in China. The government agency has never hired JPMorgan directly, securities filings and news reports suggest. Still those records indicate that the China Railway Group, the construction company whose largest customer is thought to be the Chinese government, picked JPMorgan to advise it on plans to become a public company in 2007. JPMorgan scored desired business about four years later when Ms. Zhang was an associate at the bank. The operator of a high-speed railway from Beijing to Shanghai picked the bank to guide it through its own initial public stock offering, according to news reports. In the S.E.C. document, the agency requested that JPMorgan turn over documents related to the public offering. Ms. Zhang’s father, the document noted, was detained on suspicion of corruption. To date, he has not been prosecuted. David Barboza contributed reporting. On Defensive, JPMorgan Hired China’s EliteBY BEN PROTESS AND JESSICA SILVER-GREENBERGDECEMBER 29, 2013 9:22 PM

Tang Shuangning, right, chairman of the China Everbright Group, whose son was hired by JPMorgan Chase in 2010. In a series of late-night emails, JPMorgan Chase executives in Hong Kong lamented the loss of a lucrative assignment. “We lost a deal to DB today because they got chairman’s daughter work for them this summer,” one JPMorgan investment banking executive remarked to colleagues, using the initials for Deutsche Bank. The loss of that business in 2009, coming after rival banks landed a string of other deals, stung the JPMorgan executives. For Wall Street banks enduring slowdowns in the wake of the financial crisis, China was the last great gold rush. As its economy boomed, China’s state-owned enterprises were using banks to raise billions of dollars in stock and debt offerings — yet JPMorgan was falling further behind in capturing that business. Related LinksThe solution, the executives decided over email, was to embrace the strategy that seemed to work so well for rivals: hire the children of China’s ruling elite. “I am supportive to have our own” hiring strategy, a JPMorgan executive wrote in the 2009 email exchange. In the months and years that followed, emails and other confidential documents show, JPMorgan escalated what it called its “Sons and Daughters” hiring program, adding scores of well-connected employees and tracking how those hires translated into business deals with the Chinese government. The previously unreported emails and documents — copies of which were reviewed by The New York Times — offer a view into JPMorgan’s motivations for ramping up the hiring program, suggesting that competitive pressures drove many of the bank’s decisions that are now under federal investigation. The references to other banks in the emails also paint for the first time a broad picture of questionable hiring practices by other Wall Street banks doing business in China — some of them hiring the same employees with family connections. Since opening a bribery investigation into JPMorgan this spring, the authorities have expanded the inquiry to include hiring at other big banks. Citigroup, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley have previously been identified as coming under scrutiny. A sixth bank, UBS, is also facing scrutiny, according to interviews with current and former Wall Street employees. Neither JPMorgan nor any of the other banks have been accused of wrongdoing. Still, the investigations have put Wall Street on high alert, said the current and former employees, who were not authorized to speak publicly. Some banks, they said, have adopted an unofficial hiring freeze for well-connected job candidates in China. The investigation has also had a chilling effect on JPMorgan’s deal-making in China, interviews show. The bank, seeking to build good will with federal authorities, has considered forgoing certain deals in China and abandoned one assignment altogether. The pullback comes just as JPMorgan had regained a significant share of the Chinese market. Its deal-making revived a few years after it escalated the Sons and Daughters program in 2009, an analysis of data from Thomson Reuters shows. In 2009, JPMorgan was 13th among banks winning business in China and Hong Kong. By 2013, once other banks had scaled back their Chinese business, it had climbed to No. 3. Other data shows that the bank was eighth in 2009 and — after losing market share in 2011 and 2012 — is now No. 4 in deal-making. While the hiring boom coincided with the increased business, the data does not establish a causal link between the two. Yet the Securities and Exchange Commission and federal prosecutors in Brooklyn, which are leading the JPMorgan inquiry, are examining whether the bank improperly won some of those deals by trading job offers for business with state-owned Chinese companies. The S.E.C. and the prosecutors, which might ultimately conclude that none of the hiring crossed a legal line, did not comment. JPMorgan, which is cooperating with the investigation, also declined to comment. There is no indication that executives at the bank’s headquarters in New York were aware of the hiring practices. The six other banks facing scrutiny from the S.E.C. declined to comment on the investigations, which are at an early stage. Economic forces fueled the hiring boom by Wall Street banks. An era of financial deregulation in Washington coincided with a roaring economy in China, enabling questionable hiring practices to escape government scrutiny. The hiring became so widespread over the last two decades that banks competed over the most politically connected recent college graduates, known in China as princelings. Goldman’s employee roster briefly included the grandson of the former Chinese president Jiang Zemin. And Feng Shaodong, the son-in-law of a high-ranking Communist Party official, worked with Merrill Lynch. In recent months, though, federal authorities have adopted a tougher stance toward Wall Street firms suspected of trading jobs for government business. The S.E.C. and the Brooklyn prosecutors have bolstered enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which effectively bans United States corporations from giving “anything of value” to foreign officials to gain “any improper advantage” in retaining business. JPMorgan would have violated the 1977 law if it had acted with “corrupt” intent. While the JPMorgan emails provided to federal authorities and reviewed by The Times most frequently referred to Deutsche Bank and Goldman, other banks might have also inspired JPMorgan’s hiring. Both JPMorgan and Credit Suisse, for example, did business with Fullmark, a consulting firm run by the only daughter of Wen Jiabao, then the prime minister of China. Another prized JPMorgan hire, whose father is the chairman of a state-owned financial conglomerate, previously held internships at Citigroup and Goldman. JPMorgan executives in Hong Kong also studied the hiring movements of banks with a firmer foothold in China, the documents and emails show. “Learned from GS,” one JPMorgan executive wrote in an email to colleagues, referring to Goldman Sachs’s hiring practices. JPMorgan’s legal woes extend beyond China. In November, JPMorgan struck a $13 billion settlement with government authorities over the bank’s sale of questionable mortgage-backed securities. But unlike the mortgage pact, which focused on the bank’s financial crisis-era business, the China investigations take aim at hiring practices that lasted until this year. And while the $13 billion payout involved civil settlements with various authorities, the bribery inquiry carries the threat of criminal penalties. A few top JPMorgan executives in Hong Kong have hired criminal defense lawyers, interviews show. The fallout from the investigation may also hamper the bank’s relationships with clients. As the investigation intensified in recent months, JPMorgan withdrew from a deal in which it was advising Cofco, a large state-run food company. JPMorgan offered the daughter of the company’s chairman a short-term internship in 2011, according to securities filings, and another internship in 2012. “We really need her to be back,” a JPMorgan executive in Hong Kong wrote in an email. “Her father called and emailed me.” The bank created the Sons and Daughters program in 2006 to ensure that the hiring would pass legal and regulatory muster. But then JPMorgan’s investment banking business began to lose market share in China, the data from Thomson Reuters shows. By the time JPMorgan lost the 2009 deal to Deutsche Bank, the Hong Kong executives at JPMorgan’s investment bank decided that it needed to step up its hiring. “A missed opportunity for us this year,” an executive said in an email upon learning of the loss to Deutsche Bank. “Can you guys craft a program that could work for us?” The investment banking unit experimented with a program that would have offered well-connected hires a one-year contract worth $70,000 to $100,000. The program, internal documents said, might offer “directly attributable linkage to business opportunity.” Still, some Hong Kong executives pushed for more of what they called “client referral” hiring to keep pace with rivals. “We do way, way, way too little of this type of hiring and I have been pounding on it with China team for a year,” a JPMorgan employee wrote to a colleague in a 2010 email. In that same email, the employee added: “confidential, just added son of #2 at SinoTruk to my team,” referring to a company that is part of a state-owned trucking enterprise. He added: “I got room for a lot more hires like this (Goldman has 25).” JPMorgan’s expanded program had an apparent coup when Tang Xiaoning, whose father is the chairman of the financial conglomerate China Everbright Group, was hired. Until that 2010 hiring, which has been previously reported by The Times, the bank had missed out on deal after deal from China Everbright, including one assignment that went to Morgan Stanley. But since the younger Mr. Tang was hired, China Everbright and its subsidiaries hired JPMorgan at least three times, according to Standard & Poor’s Capital IQ, a research service. When pursuing an assignment from Taikang, a life insurer that was not owned by the state, JPMorgan executives drew a similar link between hiring and deal-making. Hoping to get the nod to advise Taikang on an initial public offering of stock, emails show, JPMorgan sought to hire the chairman’s niece. But it had stiff competition. “Regarding to the juicy size, every existing active banks are trying to lobby with them,” a JPMorgan banker wrote in an email, which is unlikely to become a focus of the federal investigation, because it involves a private company. Goldman, which employed the chairman’s son, had a direct investment in the company. And the Royal Bank of Scotland was “trying to approach” the chairman’s niece, the banker wrote, “to compete us.” David Barboza contributed reporting. Hiring in China by JPMorgan Under ScrutinyBY JESSICA SILVER-GREENBERG, BEN PROTESS AND DAVID BARBOZAAUGUST 17, 2013 8:01 PM

Federal authorities have opened a bribery investigation into whether JPMorgan Chase hired the children of powerful Chinese officials to help the bank win lucrative business in the booming nation, according to a confidential United States government document. In one instance, the bank hired the son of a former Chinese banking regulator who is now the chairman of the China Everbright Group, a state-controlled financial conglomerate, according to the document, which was reviewed by The New York Times, as well as public records. After the chairman’s son came on board, JPMorgan secured multiple coveted assignments from the Chinese conglomerate, including advising a subsidiary of the company on a stock offering, records show. The Hong Kong office of JPMorgan also hired the daughter of a Chinese railway official. That official was later detained on accusations of doling out government contracts in exchange for cash bribes, the government document and public records show. The former official’s daughter came to JPMorgan at an opportune time for the New York-based bank: The China Railway Group, a state-controlled construction company that builds railways for the Chinese government, was in the process of selecting JPMorgan to advise on its plans to become a public company, a common move in China for businesses affiliated with the government. With JPMorgan’s help, China Railway raised more than $5 billion when it went public in 2007. The focus of the civil investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission’s antibribery unit has not been previously reported. JPMorgan — which has had a number of run-ins lately with regulators, including one over a multibillion-dollar trading loss last year — made an oblique reference to the inquiry in its quarterly filing this month. The filing stated that the S.E.C. had sought information about JPMorgan’s “employment of certain former employees in Hong Kong and its business relationships with certain clients.” In May, according to a copy of the confidential government document, the S.E.C.’s antibribery unit requested from JPMorgan a battery of records about Tang Xiaoning. He is the son of Tang Shuangning, who since 2007 has been chairman of the China Everbright Group. Before that, the elder Mr. Tang was the vice chairman of China’s top banking regulator. The agency also inquired about JPMorgan’s hiring of Zhang Xixi, the daughter of the railway official. Among other information, the S.E.C. sought “documents sufficient to identify all persons involved in the decision to hire” her. The government document and public records do not definitively link JPMorgan’s hiring practices to its ability to win business, nor do they suggest that the employees were unqualified. Furthermore, the records do not indicate that the employees helped JPMorgan secure business. The bank has not been accused of any wrongdoing. Yet the S.E.C.’s request outlined in the confidential document hints at a broader hiring strategy at JPMorgan’s Chinese offices. Authorities suspect that JPMorgan routinely hired young associates who hailed from well-connected Chinese families that ultimately offered the bank business. Beyond the daughter of the railway official, the S.E.C. document inquired about “all JPMorgan employees who performed work for or on behalf of the Ministry of Railways” over the last six-plus years. A spokesman for JPMorgan said, “We publicly disclosed this matter in our 10-Q filing last week, and are fully cooperating with regulators.” The Ministry of Railways, which has since been restructured into various agencies, and the China Everbright Group did not respond to requests for comment. A spokeswoman for the S.E.C. declined to comment. Attempts over the weekend to reach Ms. Zhang and Tang Xiaoning, both of whom have left JPMorgan, were unsuccessful. Western companies have been aggressive in trying to snag a share of riches in China’s fast-growing economy in recent years. Some have come under fire over their business practices there, including GlaxoSmithKline, whose employees are said by Chinese officials to have confessed to bribing doctors to increase pharmaceutical sales. Global companies also routinely hire the sons and daughters of leading Chinese politicians. What is unusual about JPMorgan is that it hired the children of officials of state-controlled companies. It is even less common for American authorities to scrutinize such practices. Only a handful of Wall Street employees have ever faced bribery accusations, including a former Morgan Stanley executive in China who pleaded guilty to criminal charges in 2012, admitting to “an effort to enrich himself and a Chinese government official.” In recent years, the S.E.C. and the Justice Department have each stepped up their enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a 1977 federal law that essentially bans United States companies from giving “anything of value” to a foreign official to win “an improper advantage” in retaining business. The S.E.C. created its own corrupt practices unit, which since 2010 has filed about 40 cases against companies like Tyco and Ralph Lauren. Over that same period, the Justice Department has leveled charges in more than 60 cases. Legal experts note that there is nothing inherently illicit about hiring well-connected people. To run afoul of the law, a company must act with “corrupt” intent, or with the expectation of offering a job in exchange for government business. “While the hire of a son or daughter itself is not illegal, red flags would be raised if the person hired was not qualified for the position, or, for example, if a firm never received business before and then lo and behold, the hire brought in business,” said Michael Koehler, an expert on the corrupt practices act who is an assistant professor at the Southern Illinois University School of Law. The inquiry into JPMorgan comes when the bank is already the focus of investigations in the United States by at least eight federal agencies, a state regulator and two foreign nations. Many of the cases, including a civil and criminal investigation in California, involve JPMorgan’s financial-crisis-era mortgage business. The multitude of cases has led some lawmakers to question whether JPMorgan, which has operations in more than 60 countries, is too big to manage. The potential perils of JPMorgan’s size also came to light with a multibillion-dollar trading blowup last year that came to be known as the “London Whale.” The trading losses, stemming from a bad bet on the exotic financial instruments known as derivatives, prompted Congressional hearings and wide-ranging investigations. On Wednesday, federal prosecutors in Manhattan and the Federal Bureau of Investigation announced criminal charges against two of the bank’s former traders in London, accusing them of masking the size of the $6 billion loss. The S.E.C., conducting a parallel investigation, is seeking to extract a rare admission of wrongdoing from the bank related to the losses. A settlement, which could come as soon as this fall, will also include a hefty fine, according to people briefed on the matter. The agency’s bribery inquiry could pose an even steeper challenge to JPMorgan. Although banks are prone to the occasional trading blunder — JPMorgan produced record quarterly profits despite the losses in London last year — a corruption inquiry could leave a more lasting mark on its reputation. It might also spur the Justice Department to open a criminal investigation. The families of the ruling elite in China see great value in finding work at Wall Street banks. While the jobs often pay token sums, finding such work bolsters the résumés of aspiring financiers and lends credibility in the Chinese business world. In the case of Mr. Tang, the S.E.C. is seeking his salary, “employment file” and “communications” he has had with JPMorgan since he left in December 2012. The agency is also requesting documents that “identify all persons involved in the decision to hire” Mr. Tang, who is believed to have joined the bank in 2010. The S.E.C.’s document appears to be looking for connections between his hiring and business JPMorgan won from the China Everbright Group and its banking subsidiary. In its confidential request, the S.E.C. asked the bank to “identify and produce all contracts or agreements between JPMorgan and China Everbright.” Before hiring Mr. Tang, JPMorgan appeared to do little if any business with China Everbright, based on a review of securities filings and news reports. Since then, though, China Everbright has emerged as one of its prized Asian clients. In 2011, its banking subsidiary hired JPMorgan as one of 12 financial advisers on its decision to become a public company. Amid global economic turmoil and questions about China’s banking system, that deal was delayed. Yet in 2012, JPMorgan was the only bank hired to advise China Everbright International, a subsidiary focused on alternative energy businesses, on a $162 million sale of shares, according to Standard & Poor’s Capital IQ, a research service. JPMorgan, according to securities filings, owns a stake in the subsidiary. The same year, JPMorgan guided China Everbright through its role in what was, according to Dealogic, the largest-ever private equitydeal in China. The deal involved reshaping Focus Media, a digital advertising firm, into a private company owned, in part, by China Everbright. The S.E.C. is investigating similar aspects of JPMorgan’s hiring of Ms. Zhang, whose father is Zhang Shuguang, former deputy chief engineer of China’s railway ministry. Before joining JPMorgan, Ms. Zhang attended Stanford University, according to her LinkedIn and Facebook pages. In addition to requesting her employment file and compensation earned from JPMorgan, the S.E.C. is asking the bank to turn over “all contracts or agreements between JPMorgan and the Ministry of Railways of the People’s Republic of China.” The Ministry of Railways has never hired JPMorgan directly, securities filings and news reports suggest. But those records indicate that the China Railway Group, the construction company whose largest customer is thought to be the Chinese government, hired JPMorgan to take it public in 2007. Ms. Zhang was hired around this time. About four years later, when Ms. Zhang was an associate at the bank, JPMorgan won out again. This time, according to media reports, the operator of a high-speed railway from Beijing to Shanghai picked the bank to steer it through its own public offering. That deal fell apart after a 2011 train collision killed 40 people and injured hundreds. The incident — just a month after the Chinese government announced the project — spotlighted the dangers of corruption in China’s railway system. The railway minister at the time, Liu Zhijun, has since received a suspended death sentence for accepting bribes in exchange for government rail contracts over a 25-year period, according to reports. Ms. Zhang’s father, the former deputy chief engineer, was also detained on suspicion of corruption, according to China’s official state-run news agency. It is unclear whether that case is still pending. The S.E.C., in its request to JPMorgan, questioned whether the bank had “investigated the reported arrest.”

|

|

|

|

| 实用资讯 | |

|

|

| 一周点击热帖 | 更多>> |

| 一周回复热帖 |

| 历史上的今天:回复热帖 |

| 2018: | 解决台湾和南海难题的最佳方案,终于有 | |

| 2018: | 床铺执政一年多,就彻底搞定ISIS 和北 | |

| 2017: | 相信太阳系各“星球”围着太阳乱转的, | |

| 2017: | 伪科学家来了!好多啊。 | |

| 2016: | 习包子山寨小不死? 水平还差点,赫赫 | |

| 2016: | 看来梁案判决当事人都不满意,所以。。 | |

| 2015: | 今天总算交了两门课的试卷,还有一门课 | |

| 2015: | Joshua:梧桐花 | |

| 2014: | 人无贫贵:尊严和品行 | |

| 2014: | 贵族的培养是从胃开始的 | |