| 中共五大戰區39個陸基基地導彈旅位置圖 |

| 送交者: Pascal 2020年09月21日16:53:12 於 [五 味 齋] 發送悄悄話 |

|

Mapping the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force by Decker Eveleth Last Updated 07/02/2020 Introduction

The People’s Republic of China processes one of the largest missile forces in the world. Ten years ago the number of Chinese missile brigades numbered around twenty to twenty-five. Today the number is closer to forty brigades, with ten of those brigades being added in the past three years. In addition to a growing force of ICBMs, the PRC also processes large numbers of accurate and nuclear-capable medium and intermediate-range missiles. These forces are organized into the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF), one of China’s five service branches. The recent reorganization of the Rocket Force and the proliferation of brigades has warranted a reexamination of its order of battle, which has grown in both numbers and capability. Part of the reason why China’s missile forces are so large is that unlike the United States and Russia, China was never bound by the terms of the recently deceased Intermediate-Range Forces Treaty (INF) Treaty, which banned missiles with ranges between 500 kilometers and 5,500 kilometers. Without such arms control in place, the PRC was free to develop a wide array of short and medium-range systems. The United States has no system equivalent to missiles like the DF-26 IRBM, which has a range of 4,000 kilometers. The last time someone attempted to compile a complete picture of China’s ballistic missile forces was over a decade ago with Sean O’Connor’s report on the Second Artillery. Because no one has released an updated dataset, scholars have had to rely on decade-old orders of battle when examining the PRC military. I’m making this dataset publicly available so that more information on China's force posture is easily accessible. I have put together an as complete as possible picture of the PLARF’s order of battle entirely with data publicly available online. The majority of my own conclusions on brigade equipment come from detail matching ground imagery released by Chinese state media or collected from Chinese social media sites like Weibo. In addition, 1980s era declassified documents from the Central Intelligence Agency yielded a surprising amount of data on active ICBM brigades. 最後更新時間為07/02/2020 介紹 中華人民共和國處理着世界上最大的導彈部隊之一。十年前,中國的導彈旅數量約為二十至二十五。如今,該旅已接近四十個旅,在過去三年中增加了十個旅。除了洲際彈道導彈的力量不斷增加外,中國還處理大量精確和有核能力的中程和中程導彈。這些部隊被編入中國人民解放軍火箭兵部隊(PLARF),這是中國的五個軍種之一。火箭部隊最近的改組和旅的擴散保證了對其戰鬥順序的重新審視,戰鬥的數量和能力都在增長。 中國導彈力量之所以如此之大的部分原因是,與美國和俄羅斯不同,中國從未受到最近去世的《中程部隊條約》(INF)條約的約束,該條約禁止射程在500公里至5500公里。如果沒有這樣的軍備控制,中國將自由發展各種短程和中程系統。美國沒有像DF-26 IRBM這樣的導彈,其射程為4,000公里。 上一次有人試圖編制中國的彈道導彈部隊的全貌是在十多年前與肖恩·奧康納對二炮報告。由於沒有人發布更新的數據集,因此學者在審查中國軍隊時不得不依靠已有十年歷史的戰鬥命令。我正在公開提供此數據集,以便可以輕鬆獲取有關中國兵力狀況的更多信息。我用網上公開可用的數據,儘可能完整地整理了PLARF的戰鬥順序。我對大隊裝備的大部分結論來自中國官方媒體發布或從微博等中國社交媒體網站收集的細節匹配地面圖像。此外,1980年代中央情報局解密的文件還產生了令人驚訝的有關洲際彈道導彈現役旅的數據。 組織 中華人民共和國於1966年組建了第二炮兵部隊,這是現代PLARF的前身。最初,這支部隊僅部署了少量核能型中程彈道導彈(MRBM)和中程彈道導彈(IRBM)。多年來,該部隊的發展是在1981年增加了孤立的洲際彈道導彈(ICBM),然後在1980年代後期引入了DF-21,這是中國第一個真正的移動導彈系統。第二炮兵部隊沒有像常規的人民解放軍地面部隊那樣向區域軍事指揮部匯報,而是直接向中央軍事委員會報告,中央軍事委員會是監督軍隊的平民共產黨組織。2015年,第二炮兵總隊改組為人民解放軍火箭兵部隊,該部隊現已成為中國武裝力量的完整分支。緊隨其後的是,已部署的旅的數量大量增加,構成了PLARF導彈旅的總數增加25-30%。 這支部隊分為七個基地,全部集中在某些地區。以前,這些基地的編號為51到56,而基地22是彈頭的存儲和處理基地。旅的編號為800年代。在2015年進行重組後,基地被重新編號為61至67,基地67是基地22的新名稱。旅也被重新編號以匹配基地。例如,在第62基地下的一個旅將標為“第62旅”。 每個基地負責監督大約六個旅。每個旅包含數千名人員,導彈發射器本身又分為由發射公司組成的發射營。每個編隊的運輸者-發射者發射器(TEL)的數量根據旅配備的導彈種類而有很大不同。例如,DF-31旅每個旅大約有十二個發射器,每個公司負責一個單獨的發射器,而DF-15旅每個旅有多達三十六個發射器,每個公司最多擁有三個發射器。 。巡航導彈旅被認為有27個TEL,IRBM旅則有大約16個。 旅基地的解剖 中國導彈旅的駐軍通常是按照我將要概述的易於識別的標準建造的,儘管該標準似乎會隨時間而變化。大多數基地都是大型的方形設施,具有清晰的安全範圍。一個行政大樓或多個行政大樓位於大樓的中心附近,大部分時間都朝着大門。在行政區域的兩側是旅房。此布局與大多數其他PLA駐軍都共享。導彈基地的真正標誌是通常位於基地後方的高架車庫和發射器車庫。高架車庫通常是一個20或30英尺高的結構,用於在室內安裝導彈,而在情報衛星視線範圍之外。附近將是導彈發射場和支援車輛的車庫。有時這些車庫成排排列,有時像甜甜圈(622)導彈基地的環形排列。在某些情況下,發射器車庫會附接到高架海灣,例如建水(625)或萊蕪(653)的車庫。

信陽666旅是PLARF旅級設施的一個相當典型的例子。一扇正門正對着一個行政大樓,兩旁是軍營建築。還提供支持車輛的車庫,軍事通訊和氣象遙測站。高架就是一個帶有發射器車庫的例子。我們可以將該高架海灣的布局(包括其窗戶和天窗圖案)與央視發布的圖像進行匹配,從而確認其作為DF-26旅的地位:

戰鬥順序 以下是PLARF當前的戰鬥順序。一共有39個旅,但另一個旅618可能最近也已經服役。一些基地具有與它們所裝備的導彈相匹配的某些角色。例如,台灣正對面的Base 61基地幾乎裝備了PLARF的所有短程彈道導彈清單。其他基地,如基地62和63,則擁有更多的導彈清單。大膽的旅被確認配備有指定的武器。 中華人民共和國將其導彈劃分為編號等級,這在一定程度上表明了其射程等級。一位數的導彈是1970年代和80年代較舊的彈道導彈。DF-4 IRBM可能仍在Sun甸(662)或通道(634)服役,而DF-5 ICBM仍在服役,其中一些已升級為DF-5C。DF-1X類由短程彈道導彈(SRBM)和巡航導彈(GLCM)組成,彈道導彈的射程低於1,000公里,巡航導彈的射程約為2,000公里。DF-2X類包括DF-21中程彈道導彈和DF-26中程彈道導彈。DF-3X和DF-4X級別只有一個導彈系統,分別是DF-31和DF-41。DF-31是一種移動式洲際彈道導彈,最初的射程僅為7 升級到DF-31A的射程為200公里,射程為11,200公里。該系統當前正在通過改進的TEL設計進行升級,即DF-31AG。DF-41是PLARF的最新移動式ICBM,其射程可達15,000公里。目前尚不清楚DF-41的基礎,但漢中(644)被認為是候選人。 部隊最近的一些顯着擴充包括部署了四個DF-26 IRBM旅,以及升級為現在配備有DF-16 SRBM的617和636旅。我們應該期望將來看到更多的DF-26旅。TEL生產現場的最新衛星圖像顯示它們仍在大量生產中。 在洲際彈道導彈領域,DF-31A旅不斷升級為新的DF-31AG TEL。值得注意的是,我們看到了DF-31A導彈的升級能力,但沒有顯着擴大其總兵力。DF-5筒倉部隊仍在服役,新型DF-5C mod導彈已於近期投入生產。據報道,DF-41洲際導彈的筒倉選項與它們的機動角色一起被考慮。這些導彈可能位於內蒙古的吉蘭泰或河南普羅維登斯的Sundian(662)。 剩餘的問題 PLARF可以採取幾個方向來發揮其洲際彈道導彈的力量。泰安特種車輛繼續生產DF-31AG TEL,但是這些TEL是用於升級現有的旅還是用於創建新的旅尚不得而知。我們已經有證據表明新組建的664旅已經裝備了DF-31AG,這可能意味着該地區的其他新旅將配備該系統。這些新型旅中的一些也可能會裝備DF-41。 PLARF可能會通過替換一些剩餘的DF-11A旅來繼續擴大DF-16 SRBM的武器庫。基地61訓練營的最新影像顯示,一架DF-11A部隊同時也配備了DF-16。目前尚不知道PLARF將在其上放置新的短程高超音速飛機DF-17的位置,但Dan州可能是候選對象。 近年來,中國人民解放軍的火箭隊經歷了大規模的擴張,在過去的三年中增加了十個或更多旅,在過去的四年中增加了三個新系統。最近的圖像在解決有關戰鬥順序的問題上已經走了很長一段路,但是與此同時,產生了更多的圖像。希望發布更多圖像可以解決許多這些問題。在我挖掘信息並進一步了解信息時,我將不斷更新此KMZ。將來,我還將把中國的導彈和TEL生產設施寫為單獨的博客文章和KMZ。 撰寫本報告時引用的作品: “中國導彈百科全書第二節:導彈及導彈設備的儲存和處理設施。” 中央情報局。https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP84T00171R000301550001-8.pdf 拜納,維納雅克。“中國媒體報道了一個可以襲擊孟買的新型導彈旅。這到底有什麼新消息?” 印刷品,2019年4月19日.https: //theprint.in/defence/china-media-reports-new-missile-brigade-hit-mumbai/50731/ 拜納,維納雅克。“中國在四川新設的秘密導彈守備所可以針對印度及其他地區。” 印刷品,2018年6月27日.https: //theprint.in/defence/chinas-new-secret-missile-garrison-in-sichuan-can-target-all-of-india-and-beyond/75347/ 博伊德,亨利。“ 2019年五角大樓報告:中國的火箭彈彈道”,國際戰略研究所軍事平衡博客,2019年5月15日。https: //www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2019/05/pla-rocket-force- 彈道 克里斯·滕森(Hris M. 中國核力量,2019,原子科學家公報,75:4,171-178,DOI:10.1080 / 00963402.2019.1628511 漢斯·克里斯滕森(Kristensen),“中國的新型DF-26導彈出現在中國東部基地。” 美國科學家聯合會,2020年1月21日.https://fas.org/blogs/security/2019/09/china-silo-df41/ 漢斯·克里斯滕森(Kristensen),“在中國核導彈訓練區看到的新型導彈發射井和DF-41發射器。” 美國科學家聯合會,2019年9月3日.https: //fas.org/blogs/security/2019/09/china-silo-df41/ Lafoy,Scott和Eveleth,Decker。“ Sundian正在進行ICBM現代化。” 軍控一根筋,2月5日2019年https://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/1208828/possible-icbm-modernization-underway-at-sundian/ 歌手Peter W.和Xiu Ma。“中國的導彈力量正在以前所未有的速度增長”,《科學》,2020年2月25日。https: //www.popsci.com/story/blog-eastern-arsenal/china-missile-force-growing/ PowerPoint在2013年11月於斯坦福大學舉行的東亞替代性核武器期貨研討會上發表的PowerPoint中,Mark A.“中國的未來核力量基礎設施” 。http: //www.npolicy.org/article_file/Nov2013-Stokes.pdf洛根, David C.“了解中國的導彈力量。” 在習近平主席重塑中國人民解放軍:評估中國的軍事改革。國防大學出版社,2019年.https: //ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/Books/Chairman-Xi/Chairman-Xi.pdf Logan,David C.解放軍火箭部隊的職業道路:他們所說的我們,亞洲安全組織,2019,15:2,103-121,DOI:10.1080 / 14799855.2017.1422089 奧康納,肖恩,“ PLA第二炮兵”,澳大利亞空中力量,2009年。最近更新於2011年。 https://www.ausairpower.net/APA-PLA-Second-Artillery-Corps.html 斯托克斯,馬克。“中國的核彈頭存儲和處理系統”,項目2049,2010年。https://project2049.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/chinas_nuclear_warhead_storage_and_handling_system.pdf 斯托克斯,馬克。《解放軍火箭部隊的領導和部隊參考》。2049項目,2018年11月30日。 斯托克斯,馬克。“廣東正在建設的第二炮兵反艦彈道導彈旅設施?” 項目2049,2010. https://project2049.net/2010/08/03/second-artillery-anti-ship-ballistic-missile-brigade-facilities-under-construction-in-guangdong/ Organization The People’s Republic of China formed the Second Artillery Corps in 1966, the precursor to the modern-day PLARF. Initially, this force deployed only small numbers of nuclear-capable medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBM) and intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBM). Over the years this force has grown with the addition of siloed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) in 1981 and then the introduction of the DF-21, the PRC’s first truly mobile missile system, in the late 1980s. Instead of deployed units reporting to regional military commands like regular People’s Liberation Army Ground Forces units do, the Second Artillery Corps reported directly to the Central Military Commission, the civilian Communist Party organization that oversees the military. In 2015 the Second Artillery Corps was reorganized into the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force, now a full branch of the PRC’s armed forces. This was immediately followed by massive increase in the number of deployed brigades, constituting a 25-30% increase in the total number of missile brigades in the PLARF. This force is organized into seven bases, which are all concentrated in certain regions. Previously, these bases were numbered 51 through 56, with Base 22 being the warhead storage and handling base. Brigades were numbered in the 800s. After the reorganization in 2015, the bases were renumbered bases 61 through 67, with Base 67 being the new designation of Base 22. Brigades were also renumbered to match their base. For example, a brigade under Base 62 will have the designation Brigade 62X. Each base supervises around six brigades. Each brigade encompasses thousands of personnel, with the missile launchers themselves being divided into launch battalions formed of launch companies. The number of transporter-erector-launchers (TEL) per formation varies greatly depending on what kind of missile the brigade is equipped with. For example, DF-31 brigades are though to have around twelve launchers per brigade, with each company being responsible for a single launcher, while DF-15 brigades have as many of thirty-six launchers per brigade and each company having up to three launchers. Cruise missile brigades are thought to have twenty-seven TELs, and IRBM brigades are thought to have around sixteen. Anatomy of a Brigade Base Chinese missile brigade garrison are usually built to an easy to identify standard that I will outline, although the standard does seem to change depending on time period. Most bases are large, square facilities with a clear security perimeter. An administration building, or multiple administration buildings, are near the center of the complex, most of the time facing the main gate. On either side of the administration area are rows of housing for the brigade. This layout is shared with most other PLA garrisons. The real signature of a missile base is the high bay garage and launcher garages usually near the back of the base. The high bay garage is usually a twenty or thirty foot tall structure used to erect missiles indoors and out of sight of intelligence satellites. Nearby will be garages for the missile launchers and support vehicles. Sometimes these garages are aligned in rows, and sometimes in a doughnut pattern, like the ones in Yuxi (622) missile base. In some cases, the launcher garages are attached to the high bay, like the ones at Jianshui (625) or Laiwu (653). Xinyang, Brigade 666, is a fairly typical example of a PLARF brigade-level facility. A single main gate faces an admin building flanked by barracks buildings. Support vehicle garages, military communications, and a weather telemetry station are also present. The high bay is an example of one with attached launcher garages. We can match the layout of this high bay, including its window and skylight pattern, to imagery released on CCTV, confirming its status as a DF-26 brigade: Order of Battle Below is the current order of battle for the PLARF. There are a total of 39 brigades, but another brigade, 618, might also have been recently commissioned. Some bases have certain roles that match the missiles they are equipped with. For example, Base 61, directly opposite Taiwan, is equipped with almost the entirety of the PLARF’s short-range ballistic missile inventory. Others, like bases 62 and 63, have much more diverse missile inventories. Bolded brigades are confirmed to be equipped with the specified armament. The PRC designates its missiles in numbered classes that are somewhat indicative of their range class. Missiles in the single digits are the older 1970s and 80s era ballistic missiles. The DF-4 IRBM might still be in service at Sundian (662) or Tongdao (634), while the DF-5 ICBM is most definitely still in service with some being upgraded to the DF-5C. The DF-1X class constitutes short-range ballistic missiles (SRBM) and cruise missiles (GLCM), with ranges below 1,000 kilometers for ballistic missiles, and around 2,000 kilometers for cruise missiles. The DF-2X class encompasses both the DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile and the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile. The DF-3X and DF-4X class each only have one missile system, the DF-31 and DF-41 respectively. The DF-31 is a mobile ICBM that originally had a range of only 7,200 kilometers before being upgraded to the DF-31A, which has a range of 11,200 kilometers. This system is currently being upgraded with an improved TEL design, the DF-31AG. The DF-41 is the PLARF’s newest mobile ICBM, which could have a range up to 15,000 kilometers. The basing for the DF-41 is currently unknown, but Hanzhong (644) has been noted as a candidate. Some recent notable expansions to the force include the deployment of four DF-26 IRBM brigades and the upgrades to brigades 617 and 636, which are now armed with the DF-16 SRBM. We should expect to see more DF-26 brigades in the future. Recent satellite imagery of TEL production sites show that they are still being produced in large numbers. In the realm of intercontinental ballistic missiles, DF-31A brigades continue to be upgraded to the new DF-31AG TEL. It is worth noting that we have seen upgrades, but not a significant expansion of the total force of DF-31A missiles. The DF-5 silo force remains in service, with the new DF-5C mod missile having gone into production quite recently. A silo basing option for the DF-41 ICBM is reportedly being considered alongside their mobile role. These missiles may be based in Jilantai in Inner Mongolia or at Sundian (662) in Henan Providence. Remaining Questions There are several directions the PLARF could take their ICBM force. Tai’an Special Vehicle continues to produce the DF-31AG TEL, but whether these TELs are for upgrading existing brigades or are for the creation of new brigades is unknown. We already have evidence that the newly formed Brigade 664 has been armed with the DF-31AG, which might mean that the other new brigades in the area will be equipped with that system. It’s also possible that some of these new brigades will be equipped with the DF-41. The PLARF will probably continue to expand its arsenal of DF-16 SRBMs, probably by replacing some of their remaining DF-11A brigades. Recent imagery out of base 61’s training garrison shows a DF-11A unit with DF-16s present as well. Where the PLARF will put their new short-range hypersonic, the DF-17, is currently unknown, but Danzhou is a possible candidate. The People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force has undergone a massive expansion in recent years, adding ten or more brigades in the last three years and three new systems in the last four. Recent imagery has gone a long way in clearing up questions about the order of battle, but at the same time has produced many more. Hopefully, the release of further imagery will clear up many of these questions. I will continually update this KMZ as I dig up information and further information comes to light. In the future I will also write up the PRC’s missile and TEL production facilities as a separate blog post and KMZ. Works Cited in the Production of This Report: “Chinese Missile Encyclopedia Section II: Missile and Missile Equipment Storage and Handling Facilities.” Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP84T00171R000301550001-8.pdf Bhat, Vinayak. "China media reports a new missile brigade that can hit Mumbai. What’s really new about it?" The Print, April 19th 2019. https://theprint.in/defence/china-media-reports-new-missile-brigade-hit-mumbai/50731/ Bhat, Vinayak. “China’s new, secret missile garrison in Sichuan can target all of india and beyond.” The Print, June 27th 2018. https://theprint.in/defence/chinas-new-secret-missile-garrison-in-sichuan-can-target-all-of-india-and-beyond/75347/ Boyd, Henry. “2019 Pentagon Report: China’s Rocket Force Trajectory” Military Balance Blog, International Institute of Strategic Studies, May 15th 2019. https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2019/05/pla-rocket-force-trajectory Kristensen, Hans M. and Korda, Matt. Chinese nuclear forces, 2019, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 75:4, 171-178, DOI: 10.1080/00963402.2019.1628511 Kristensen, Hans M. “China’s New DF-26 Missile Shows Up At Base in Eastern China.” Federation of American Scientists, January 21st 2020. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2019/09/china-silo-df41/ Kristensen, Hans M. “New Missile Silo and DF-41 Launchers Seen in Chinese Nuclear Missile Training Area.” Federation of American Scientists, September 3rd 2019. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2019/09/china-silo-df41/ Lafoy, Scott and Eveleth, Decker. “Possible ICBM Modernization Underway at Sundian.” Arms Control Wonk, February 5th 2019. https://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/1208828/possible-icbm-modernization-underway-at-sundian/ Singer, Peter W. and Xiu, Ma. "China’s Missile Force is Growing at an Unprecedented Rate", Popular Science, Febuary 25th 2020. https://www.popsci.com/story/blog-eastern-arsenal/china-missile-force-growing/ Stokes, Mark A. “China’s Future Nuclear Force Infrastructure”, PowerPoint presented at the East Asian Alternative Nuclear Weapons Futures Workshop at Stanford University, November 2013. http://www.npolicy.org/article_file/Nov2013-Stokes.pdf Logan, David C. “Making Sense of China’s Missile Forces.” In Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms. National Defense University Press, 2019. https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/Books/Chairman-Xi/Chairman-Xi.pdf Logan, David C. Career Paths in the PLA Rocket Force: What They Tell Us, Asian Security, 2019, 15:2, 103-121, DOI: 10.1080/14799855.2017.1422089 O’Connor, Sean, “PLA Second Artillery Corps”, Air Power Australia, 2009. Last updated 2011. https://www.ausairpower.net/APA-PLA-Second-Artillery-Corps.html Stokes, Mark. "China's Nuclear Warhead Storage and Handling System", Project 2049, 2010. https://project2049.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/chinas_nuclear_warhead_storage_and_handling_system.pdf Stokes, Mark. "PLA Rocket Force Leadership and Unit Reference." Project 2049, November 30th 2018. Stokes, Mark. “Second Artillery Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile Brigade Facilities Under Construction in Guangdong?” Project 2049, 2010. https://project2049.net/2010/08/03/second-artillery-anti-ship-ballistic-missile-brigade-facilities-under-construction-in-guangdong/ https://www.aboyandhis.blog/post/mapping-the-people-s-liberation-army-rocket-force

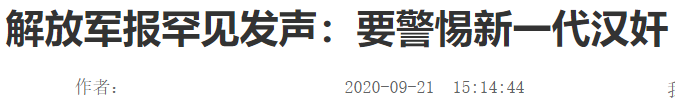

一個有自省精神的民族,才有遠大的未來。 應該說,“漢奸現象”就是抗戰期間中華民族最大的“痛點”。我們讚美近代中國百年沉淪後的民族覺醒達到了空前的程度,無數中華義士用生命和鮮血譜寫了氣壯山河的反抗外來侵略的英雄史詩,但也不能忘記,在中華民族最危險的時候,多少民族敗類變節投降、賣國求榮,認賊作父、助紂為虐,在中國歷史上留下了奇恥大辱的一筆。直到今天,抹黑英雄、洗白叛徒、為漢奸“翻案”的奇談怪論,仍在挑戰我們的價值和道德底線。 歷史因多元、複雜而愈顯其波瀾壯闊。重新審視歷史的創痛,晾曬民族蟲蠹發霉的一面,深刻反省“漢奸現象”,徹底掃除美化漢奸的霧靄,對於培塑國人的民族氣節和民族精神,牢固確立社會主義核心價值觀,凝聚起實現中國夢強軍夢巨大精神力量,無疑具有重要的歷史意義和現實價值。 電影《地道戰》裡有一個耐人尋味的場景——民兵隊長高傳寶在大槐樹下敲鐘傳達情報:來犯的有“一百多鬼子,二百多偽軍……”對這一傳為笑談的鏡頭,我們又怎能一笑了之? 要說“漢奸”,顧名思義得從漢朝講起。據清人《漢奸辨》雲,“中國漢初,始防邊患,北鄙諸胡日漸構兵。由是漢人之名,漢奸之號創焉。” 作為一個王朝,“漢”成了中國第一個具有帝國形式的穩定實體,作為帝國子民一個文化符號——“漢人”,其奸細自然被稱為“漢奸”。 漢奸是一個特定的歷史概念。按照《辭海》定義,漢奸原指漢族之變節敗類,後演變為“中華民族中投靠外國侵略者,甘心受其驅使,出賣祖國利益的人”。 漢奸,可以說是我們民族歷史上永難消除的一塊傷疤。兵荒馬亂的戰爭年代已經漸行漸遠,但曾給國家民族帶來深重災難的“漢奸現象”並未絕跡。 君不見,就在我們現實生活中,一些人繼承了漢奸先輩的衣缽,成為出賣民族利益的新一代“經濟漢奸”“政治漢奸”“網絡漢奸”等。 君不見,西方國家搞“顏色革命”和“政治轉基因”工程愈演愈烈,一些政治上的意志薄弱者和利慾薰心的貪婪之徒,已經或正在成為敵對勢力捕獵對象。 君不見,今天的中國產生漢奸的土壤仍然肥沃,“漢奸理論”“漢奸思維”並未清除,甚至在新形勢下有了某種“創新發展”。 歷史掀開了新的一頁。作為一種社會贅瘤,“漢奸現象”應時而生、應時而滅,而我們剷除滋生漢奸的土壤,同“漢奸現象”作鬥爭正未有窮期! (原標題:解放軍報長篇署名文章:《歷史的拷問》) https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/kwP5dY2hD-qVPiRuu9QHfw? |

|

|

|

|

| 實用資訊 | |

|

|

| 一周點擊熱帖 | 更多>> |

| 一周回復熱帖 |

| 歷史上的今天:回復熱帖 |

| 2019: | 李嘉誠公開回復國人:不要用空洞的道德 | |

| 2019: | 李嘉誠做的是合法的權錢交易 | |

| 2018: | 通過制裁對抗美國的對手的法案 | |

| 2018: | xpt美國開始制裁中國軍隊 | |

| 2017: | 從傑弗遜和女奴情史看國父與美國奴隸制 | |

| 2017: | 三胖子如果不再搗蛋, 唐老鴨就不再喊 | |

| 2016: | 武松有權執行死刑。按照西洋的法律觀, | |

| 2016: | 抗戰「匯總表」國際縱橫 | |

| 2015: | 在中國導彈面前,任何海軍艦船都是活棺 | |

| 2015: | 好戲連台:人大教授發公開信與弟子斷絕 | |